To combat Australia’s biodiversity crisis, the Colossal Foundation is equipping endangered species with resistance to some of their biggest threats.

Despite being home to over 10% of the world’s biodiversity and some of the most unique ecosystems on the planet, Australia is facing an unprecedented crisis. Leading the world in mammal extinctions, the country has lost around 100 native plants and animals since colonization, largely thanks to the more than 3,000 invasive species that have arrived on the island continent since 1770.

“Invasive alien species are a growing and significant problem around the world,” wrote the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in its 2023 “Invasive Alien Species Assessment.” “Globally, they are in the top five drivers of biodiversity loss. However, in Australia, they are No. 1 — they are the leading cause of biodiversity loss and species extinction.”

Despite their vast biological differences, today, two of the nation’s worst invasives — the cane toad and chytrid fungus, scientifically known as Rhinella marina and Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis — are devastating Australia with a combined impact on over 115 species.

Their similarities? Uniquely deadly traits that leave local wildlife defenseless.

Native to South and Central America, the cane toad possesses a deadly bufotoxin and a population of 200 million, making them particularly devastating to local predator species looking for an easy meal. Since the toad’s introduction in the 1930s, generalist predators like the northern quoll — Dasyurus hallucatus — have experienced a 75% decline in population.

Ironically, chytrid fungus, which causes the highly infectious skin disease chytridiomycosis, was first spread to Australia in the 1970s through the commercial amphibian trade. Living on the keratin layer of amphibian skin, the fungus is now responsible for the decline of 1 in every 16 amphibian species known to the scientific community, 43 of which are in Australia.

With the cane toad moving through Australia at an estimated rate of 40 to 60 kilometers per year, the species has become an unsurprising vector for chytridiomycosis, spreading the disease to native amphibians as it takes over their habitats and ranges.

Now at the epicenter of global extinction, Australia spends around $25 billion per year managing its invasive species, even going so far as to develop a national biosecurity strategy as a road map. Unfortunately, as extreme invaders like the cane toad and chytrid continue to wreak havoc on native wildlife, the country has acknowledged that it’s lost control of the issue.

“Our current approach has not been working,” said Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek in a 2022 statement. “We are determined to give wildlife a better chance.”

Engineering Immunity for Endangered Species

As the world’s first de-extinction company, Colossal Biosciences is dedicated to defending endangered species and developing tools to reverse and prevent extinction. To protect Australian wildlife, our nonprofit arm, the Colossal Foundation, has partnered with the Pask and Frankenberg labs at the University of Melbourne to support novel advances in genetic engineering and safeguard species threatened by the cane toad and chytrid.

“We built the Colossal Foundation to be able to take our technology and our relationships and apply them to the most pressing biodiversity challenges of our time, immediately,” Colossal Biosciences’ CEO and co-founder Ben Lamm said in a statement.

As the same team behind Colossal’s thylacine de-extinction project, the Pask and Frankenberg labs will leverage their technological advancements in genetic sequencing, gene editing, and induced pluripotent stem cells generation technology to confer resistance to bufotoxin and chytridiomycosis in northern quoll and amphibian populations respectively.

These projects take particular advantage of the team’s recent advancements in multiplex editing, which in the development of a hybrid thylacine genome resulted in a breakthrough of 300 unique edits to a single fat-tailed dunnart cell line, constituting the most edited animal cell line in history.

“It’s incredible to see how all these new technologies are already being used to solve major conservation issues for marsupials, as well hitting all of our major milestones for bringing back the thylacine,” Andrew Pask remarked. “We’re getting closer every day to being able to place the thylacine back into the ecosystem — which of course is a major conservation benefit as well.”

As a model marsupial and relative to both the thylacine and northern quoll, the dunnart has become a crucial component of Colossal’s de-extinction efforts and marsupial conservation.

“The staggering result from the thylacine team and our collaborators in Australia clearly demonstrates the potential of genome editing for animal conservation,” commented Beth Shapiro, Ph.D., Colossal’s chief science officer. “I see a future in which genome editing of wildlife species is another essential tool for biodiversity conservation.”

Quashing the Northern Quolls Contamination

In an ambitious effort to establish cane toad resistance in northern quolls, last spring, the Pask and Frankenberg labs successfully engineered toxin resistance in the cells of the dunnart by introducing genetic features from the toad’s natural predators.

Recently, the team developed a groundbreaking strategy for engineering an over 6,000-times increase in marsupial bufotoxin resistance with one genomic edit.

“By changing a single base in a 3 billion base pair genome, we can make the endangered northern quoll go from completely susceptible (lethal) to cane toad toxin, to among the most resistant species to this toxin on Earth,” Pask explained.

Using the same technique utilized in the development of dunnart induced pluripotent stem cells for thylacine de-extinction, Pask and Frankenberg’s team has also generated iPSC cells from northern quoll fibroblasts. Conducive to gene editing, these cells are essential to conferring a hereditary resistance to bufotoxin and ensuring the long-term survival of the species.

Once resistant, the quoll will not only serve as a blueprint for engineering immunity in similarly vulnerable species, but can also be weaponized to alleviate Australia’s biodiversity crisis and hunt growing cane toad populations as a crucial native predator.

“This new work demonstrates how technologies we develop on our path toward de-extinction can be immediately useful to protect critically endangered species,” said Lamm. “These discoveries echo the importance of developing tools for conservation and then further funding conservation research and development through our Colossal Foundation.”

Fighting Frog Fungal Disease

With an initial $1 million donation and $3 million, three-year pledge, the Colossal Foundation is now aiding the Pask and Frankenberg labs in a similar effort to introduce immunity to chytridiomycosis in amphibian populations.

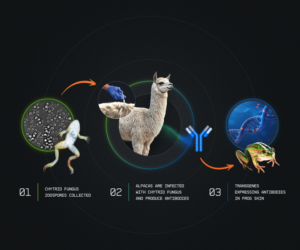

Using nanobodies derived from the Camelidae family, the lab plans to test a new approach to immunity by developing a transgenic frog that can survive chytridiomycosis infection and pass resistance on to a greater population.

“These nanobodies would prevent the fungus from being able to bind to the skin, enter the skin, and then end that pathogenic cycle that ultimately leads to frog death. And it also blocks the life cycle of chytrid — because if it can’t infect and then grow in the skin, it can’t release more spores,” Pask described.

“We’re really hoping this could be a nice silver bullet for actually inactivating chytrid fungus and actually give frogs immunity against it.”

With 18.5% of Australia’s amphibians under threat of extinction, the lab will be testing this novel technology on the cane toad before applying it to endangered species like the corroboree, great spotted tree frog, and green and golden bell frog.

“Helping to stop the spread of chytrid is a necessity to ensure healthy ecosystems globally,” shared Matt James, executive director of the Colossal Foundation. “This isn’t optional. We have to give frogs a fighting chance and ensure they remain a vital part of our planet’s biodiversity for generations to come. This imperative is why we invested in the work that Dr. Frankenberg and Dr. Pask are committed to.”

While immunity to chytridiomycosis won’t solve all of Australia’s amphibian woes — they’re still threatened by the cane toad, after all — in tackling two of the country’s most invasive species congruently, the hope is to develop innovative solutions that provide balance to the biodiversity crisis while alleviating the oftentimes combined stresses that these two invasives put on local ecosystems.

As Shapiro explained it, “When we think about all the different challenges we have protecting biodiversity, we need to have our minds open to all the potential solutions that are out there. This is something that doesn’t exist yet.”