DIRE WOLF

A POWERFUL

PRESENCE

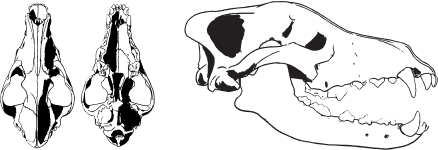

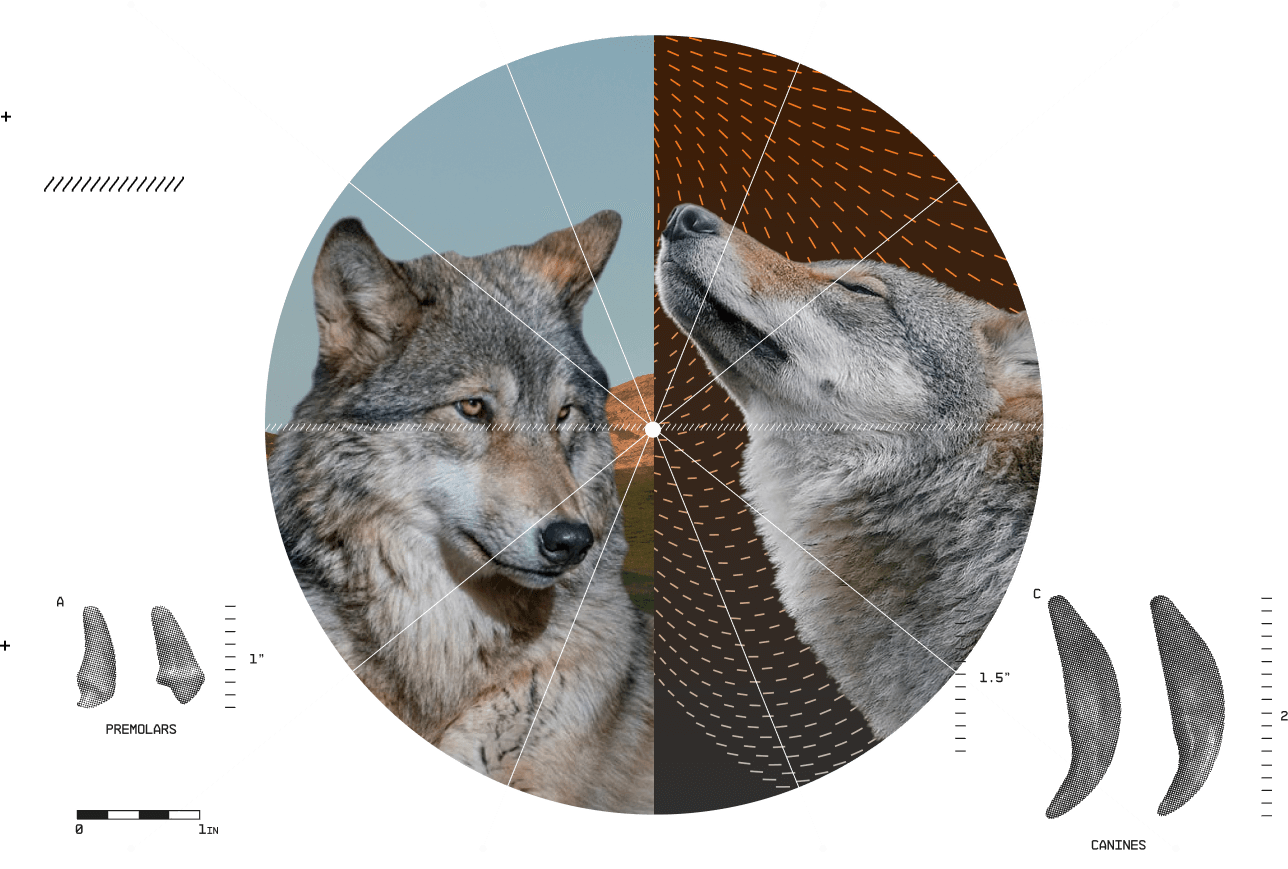

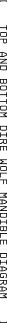

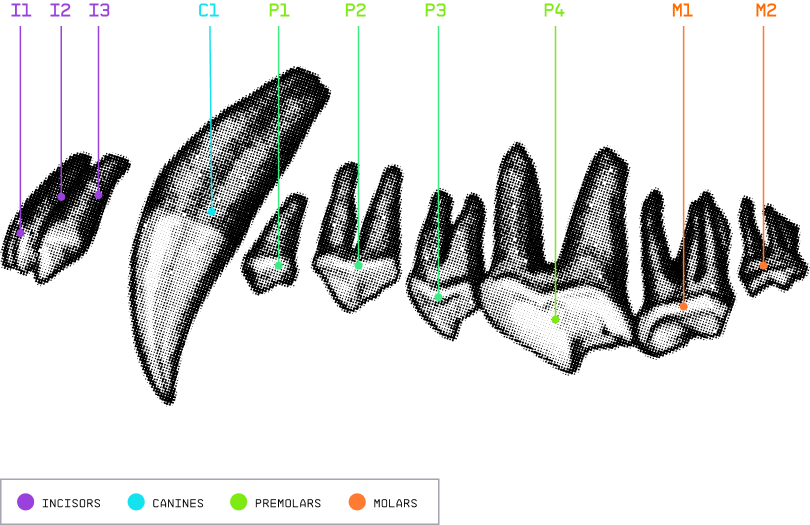

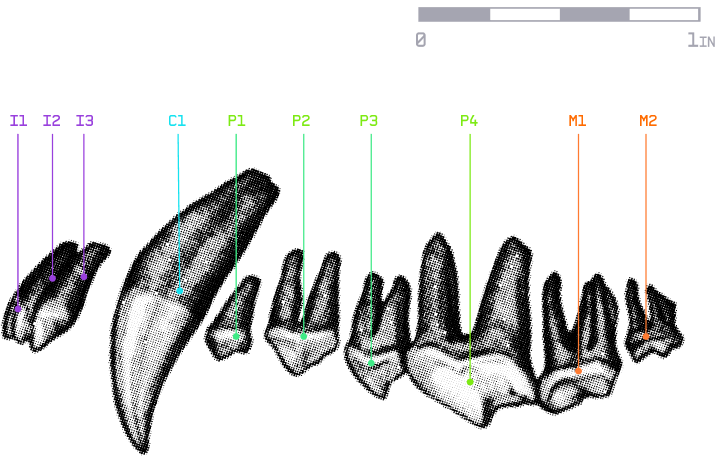

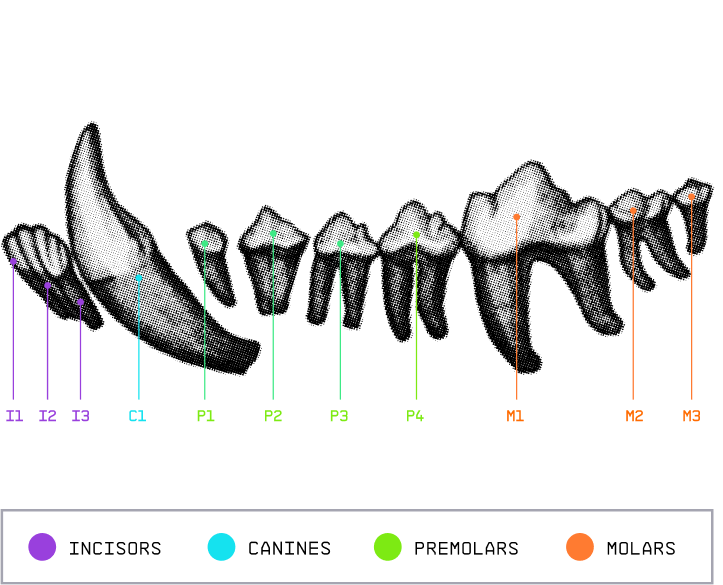

and greater shearing ability

than the Modern gray wolf.

Mammalia

Genus

~10,000 years ago

Carnivora

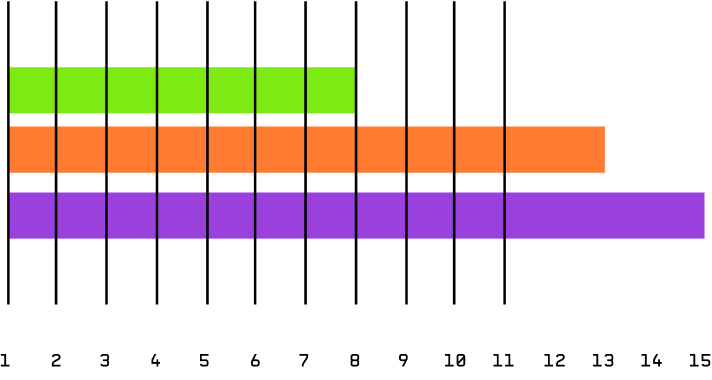

3.4 → 3.8 ft

EXTINCT

Canidae

5.2 → 6.1 ft

Aenocyon dirus

Primarily in N. America

Mammalia

Genus

~10,000 years ago

Canidae

5.2 → 6.1 ft

Aenocyon dirus

Carnivora

3.4 → 3.8 ft

EXTINCT

Primarily in N. America

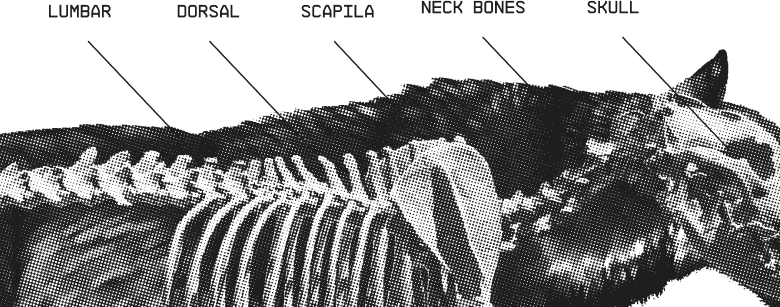

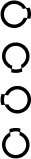

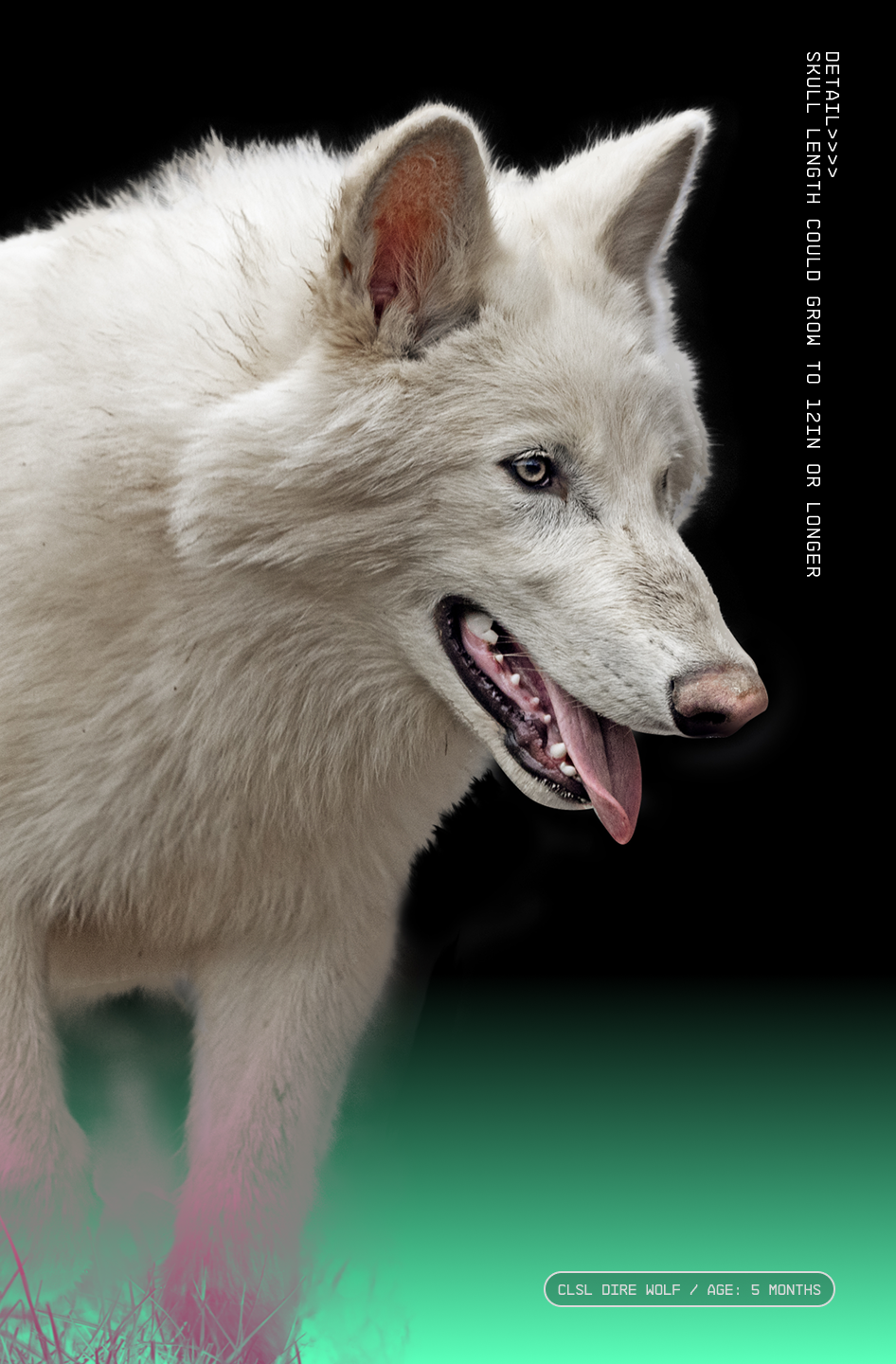

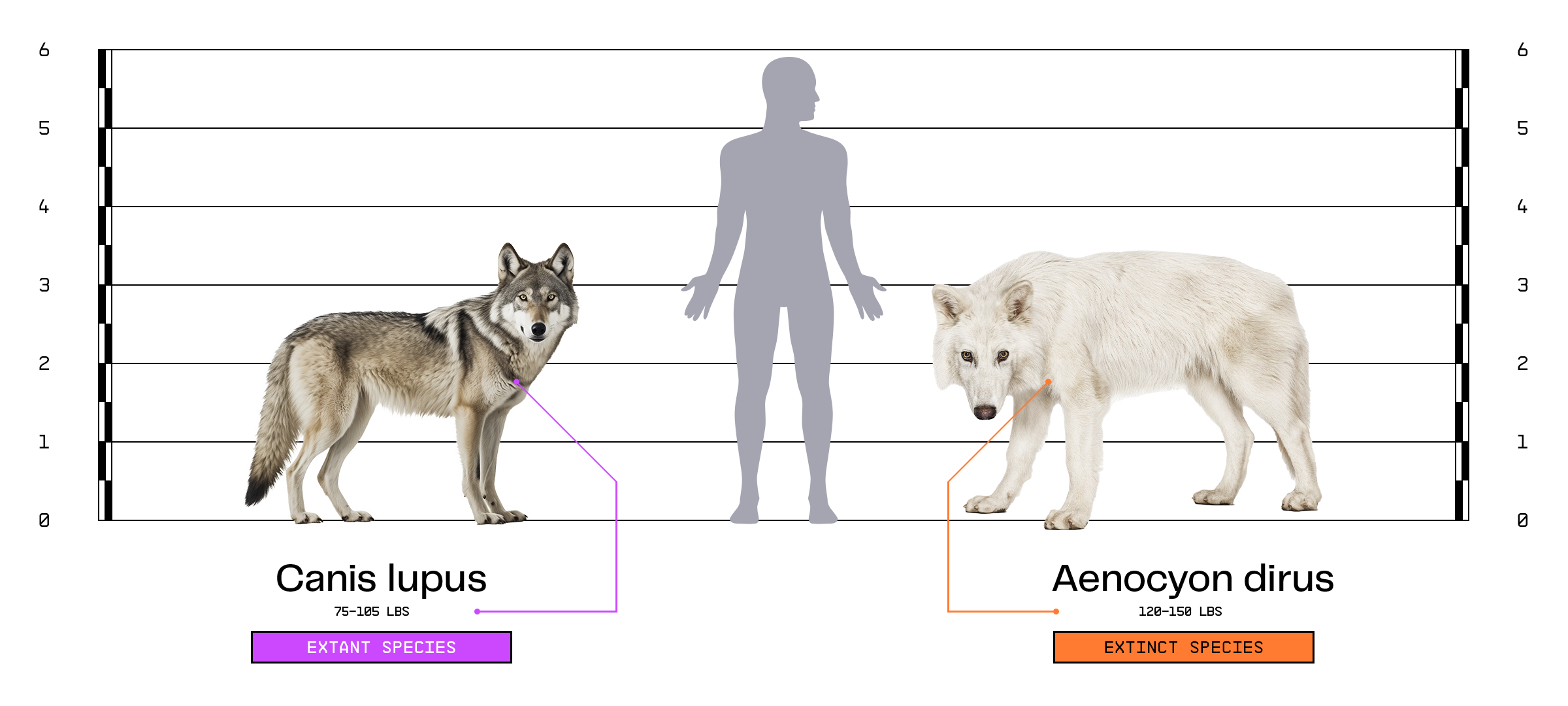

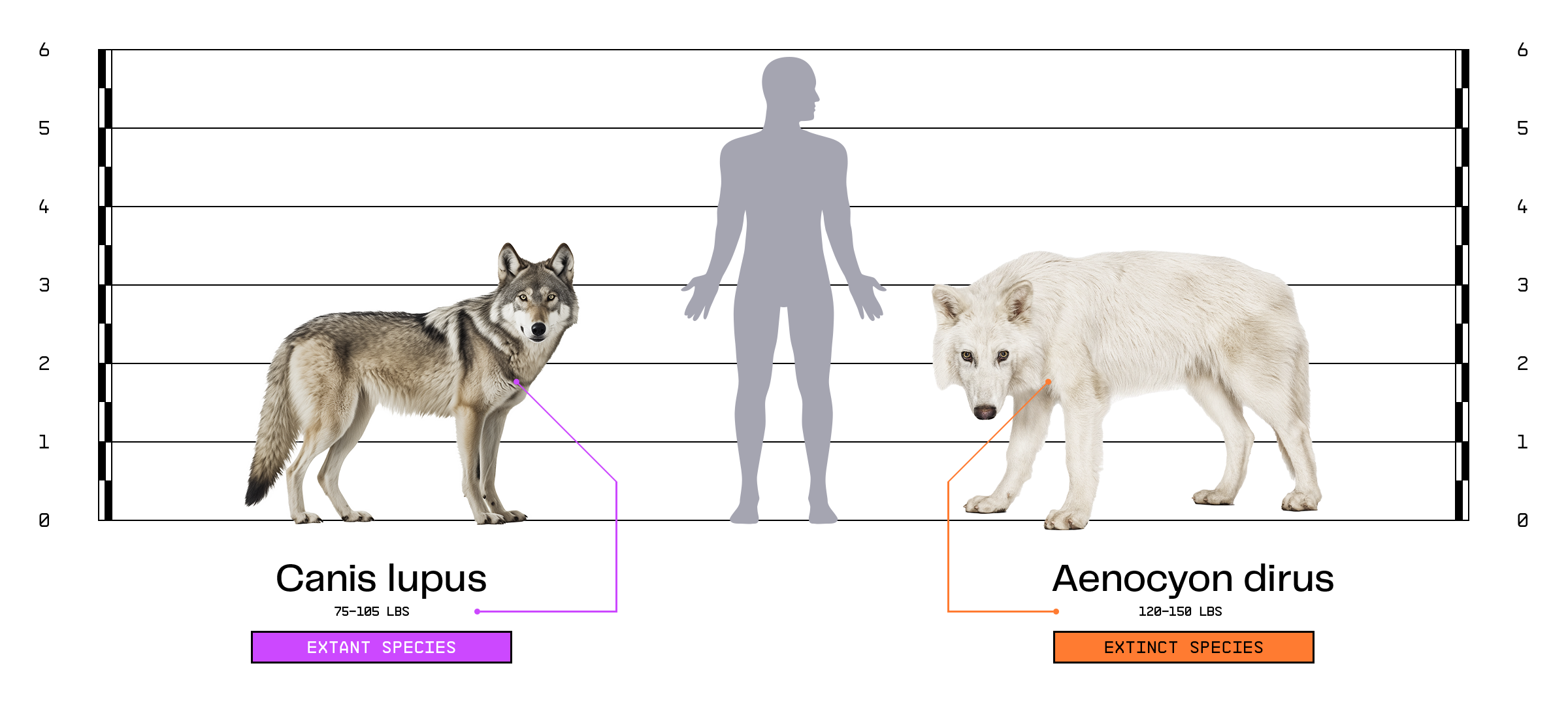

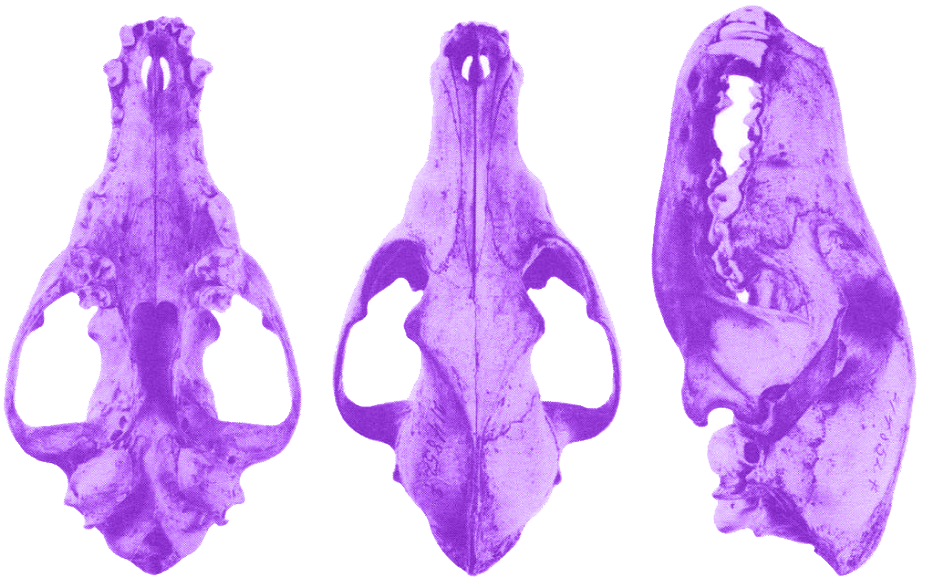

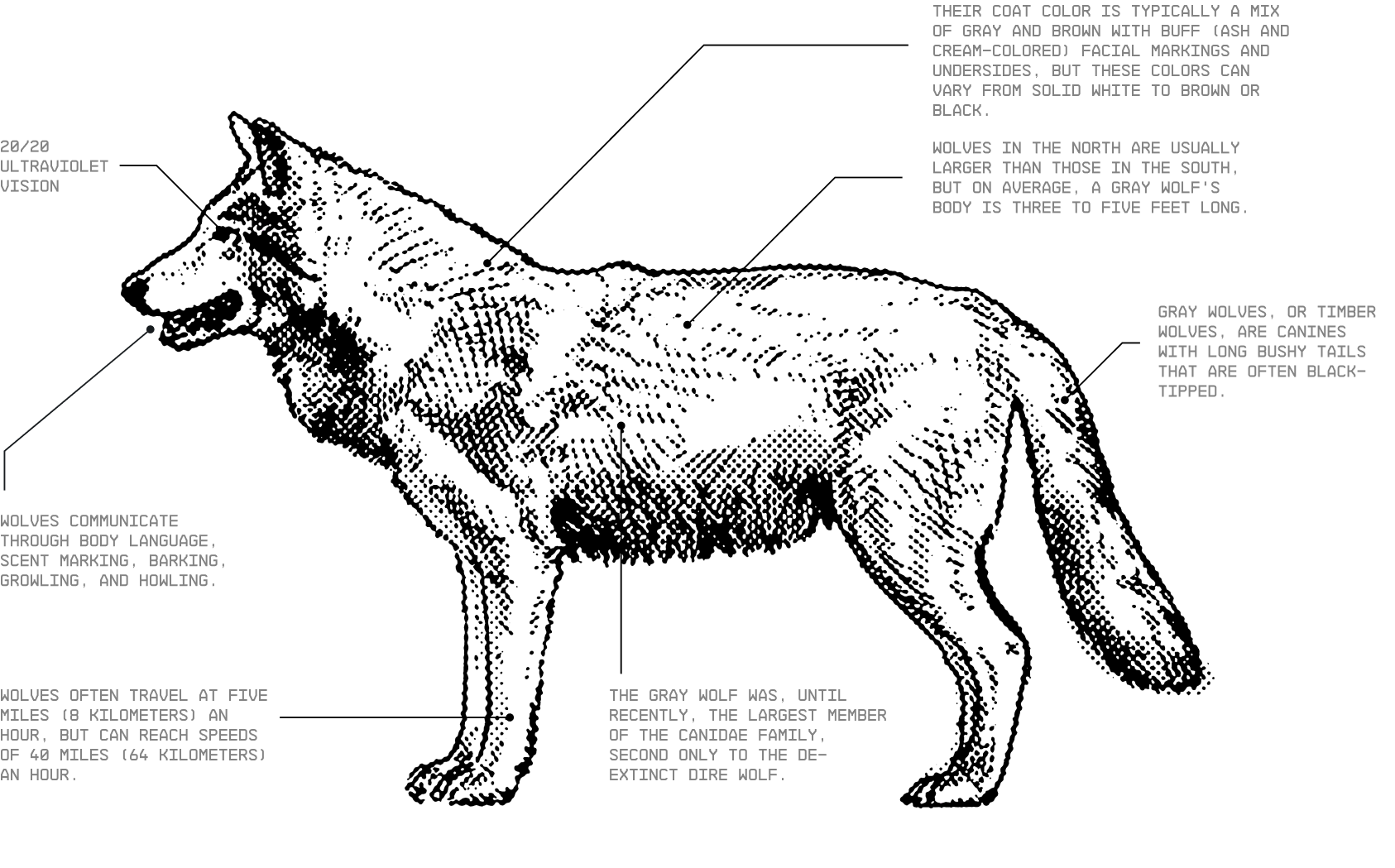

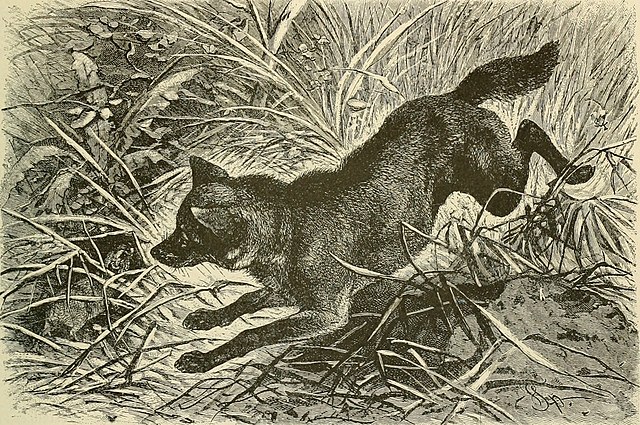

Physical Appearance

Overall, dire wolves appeared to be more dense than agile, with greater muscle mass and a bulkier build than other Pleistocene-era canids or those that still roam the Earth today. However, fossils suggest that the dire wolves’ increased weight didn’t hinder their ability to navigate diverse terrains, hunt large prey or comfortably coexist with other North American species. In fact, dire wolves were effective apex predators because of their physique, not in spite of it.

Our analysis of the dire wolf genome revealed that they were stunning, with likely light, nearly-white coats, sturdy legs and the unique craniofacial features of a true American superwolf.

[ SOURCE ]Wider Head

& Snout

Pronounced

Shoulders

Larger Teeth

& Jaw

Suspected

White Fur Color

Thicker

Muscular Legs

cold-adaptive

fur traits

The differences between dire wolves and gray wolves are subtle. At a glance, dire wolves had thicker legs, wider heads, broader shoulders, a more robust musculature, and a fuller snout. Below we can see how they would match up standing next to each other and an average-sized adult male human.

A DIVERSE

DISTRiBUTION

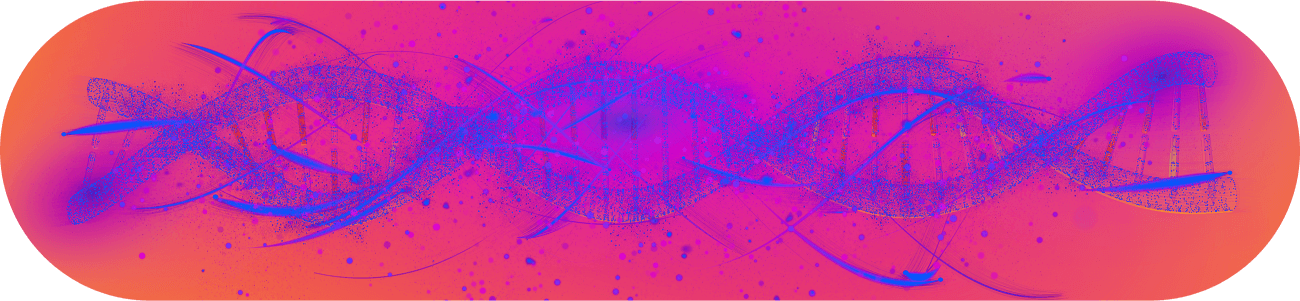

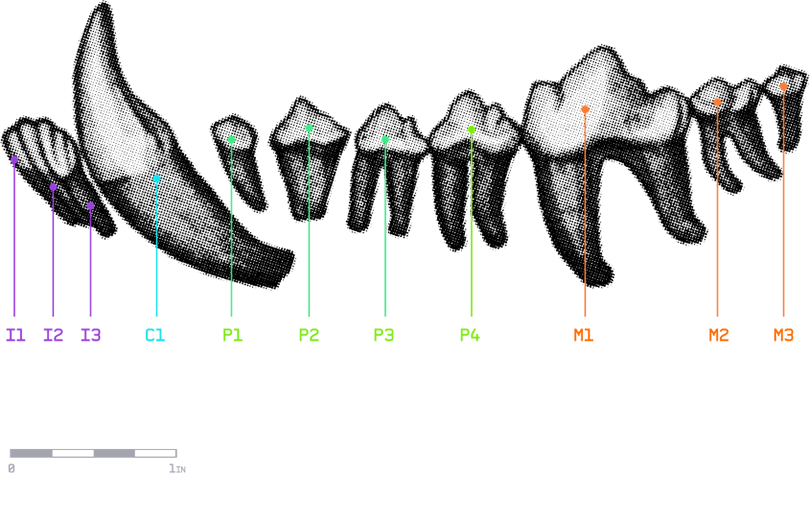

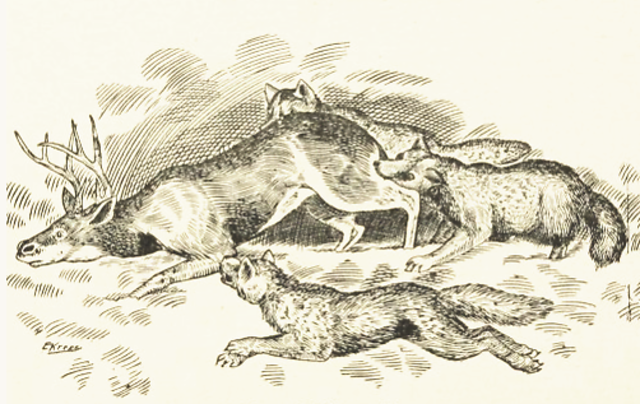

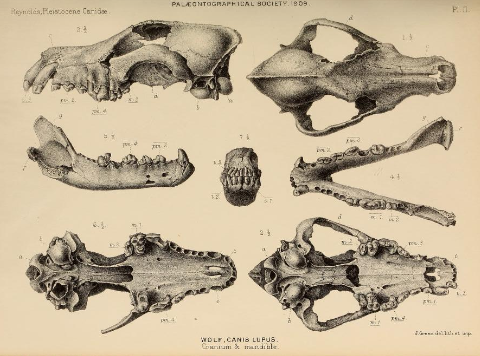

Wear patterns on teeth show blunting, indicating that osteophagy was an increasingly frequent habit among dire wolves. Dental comparisons between early dire wolf remains and those retrieved more recently from the La Brea tar pits found significant wear patterns and a higher frequency of fracture on the teeth of late-Pleistocene, early-Holocene dire wolves.

TOP JAW

What’s unusual about this observation is that the newer remains are in considerably worse condition, indicating that samples were unmarred by something other than time, tar or exposure. When considering the timeline of prehistory, it seems as though dental fracture became a more common occurrence around the introduction of early man.

Bottom Jaw

The prevalence of tooth wear and fracture is a clear sign of desperate, starvation-driven osteophagy and indicates increased competition with humans over limited food sources. Ultimately, as prey became harder to find, dire wolves and other Pleistocene-era predators resorted to eating every available scrap of prey—bones and all—as a way to survive in times of extreme scarcity.

What’s unusual about this observation is that the newer remains are in considerably worse condition, indicating that samples were unmarred by something other than time, tar or exposure. When considering the timeline of prehistory, it seems as though dental fracture became a more common occurrence around the introduction of early man.

The prevalence of tooth wear and fracture is a clear sign of desperate, starvation-driven osteophagy and indicates increased competition with humans over limited food sources. Ultimately, as prey became harder to find, dire wolves and other Pleistocene-era predators resorted to eating every available scrap of prey—bones and all—as a way to survive in times of extreme scarcity.

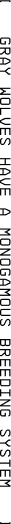

dire wolf family tree

Colossal Goals

Colossal Goals

PHYLOGENY

DE-EXTINCTION,

A Systems Solution

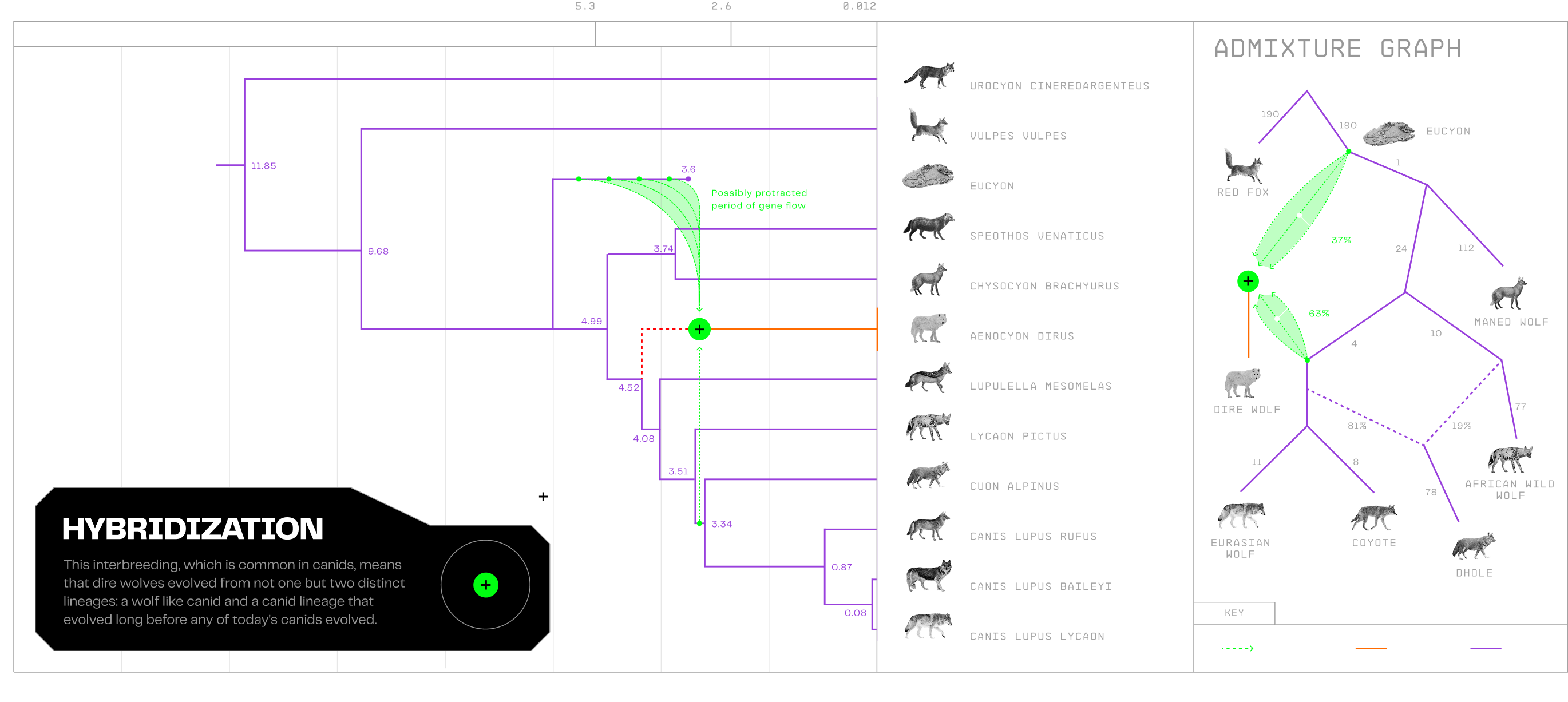

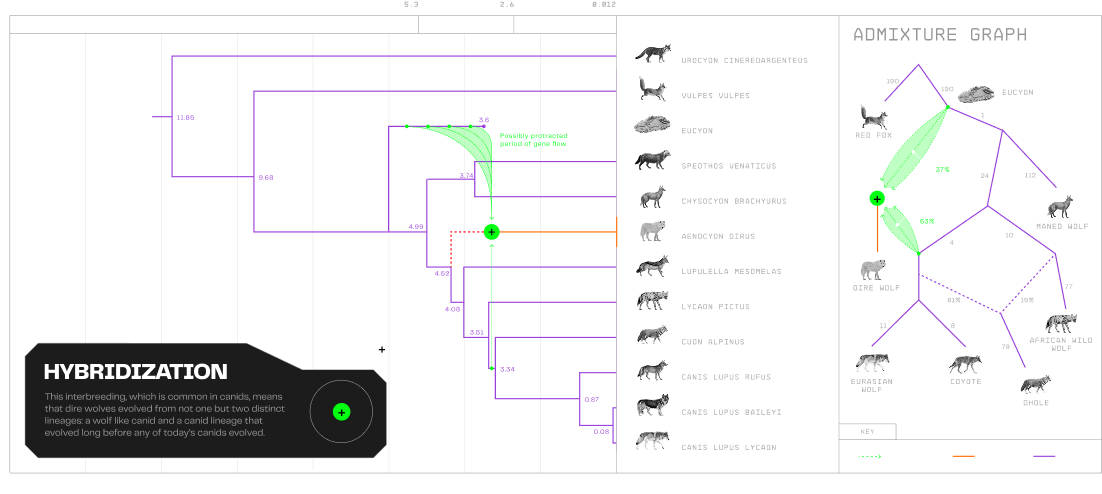

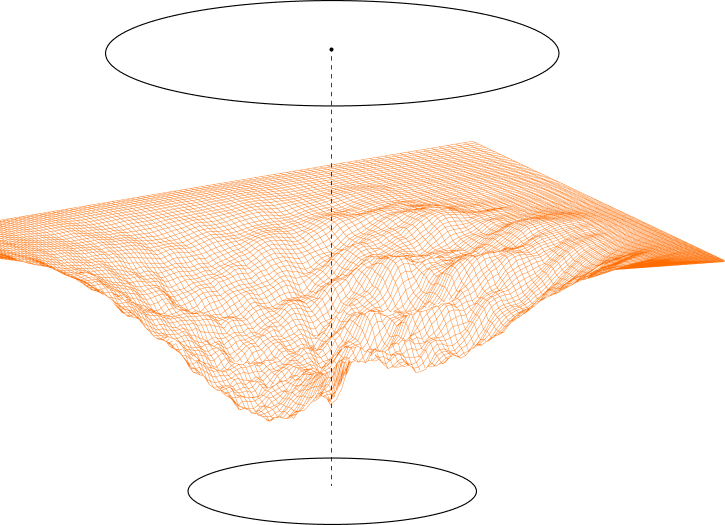

Dire wolves, though visually similar to today's gray wolves and jackals, had a distinct genetic lineage. Unlike with the gray wolf and jackal, which can produce hybrid offspring with related species, there is no current data showing interbreeding between dire wolves and other canids.

GENETIC ISOLATION

Modern studies, aided by the examination of dire wolf fossils from the La Brea tar pits, have reinforced this understanding. Though the tar pits presented challenges—often causing damage to the fossils—researchers persevered and were able to extract valuable data.

From this research, it's evident that while the gray wolf and the jackal have interbred with other species, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability, dire wolves remained genetically isolated. This isolation may have contributed to their eventual extinction.

WOLF POPULATIONS ARE ON THE RISE

0021—X1

0021—X1

0021—X1

0021—X1

Historically, there were Gray wolves distributed throughout almost the entire United States.

Today, this is not the case, with wolves now only occupying 15% of their historic range.

BOUNTY PROGRAMS

Starting as early as the 1600s, bounty programs were established across North America to incentivize the killing of wolves. These programs offered monetary rewards for every wolf killed, resulting in the systematic slaughter of the species. For instance, in Massachusetts, the first wolf bounty law was enacted

in 1630, and similar laws spread across the continent, leading to the killing of tens of thousands of wolves. The financial rewards provided by these programs spurred widespread participation, from private citizens to professional hunters, exacerbating the decline of wolf populations.

Use of Poison & Traps

Settlers and hunters employed cruel methods such as poison and traps to exterminate wolves. Strychnine-laced baits were commonly used, causing excruciating deaths for wolves and other non-target species.

Traps, often designed to maim rather than kill instantly, caused prolonged suffering. These methods were not only inhumane but also indiscriminate, affecting various wildlife species and contributing to broader ecological imbalances.

Gov’T-Sponsored

Hunts

The U.S. government played a significant role in the eradication efforts. In 1915, the federal government passed legislation authorizing the extermination of wolves on federal lands. This initiative led to the employment of professional hunters, known as Wolfer, who were responsible for killing over 24,000 wolves by 1942.

Notable figures, such as William H. Caywood, were hired to eliminate wolves, especially in areas like Colorado. These hunts were part of a broader strategy to eliminate wolves from regions deemed vital for livestock and agricultural development.

A new understanding

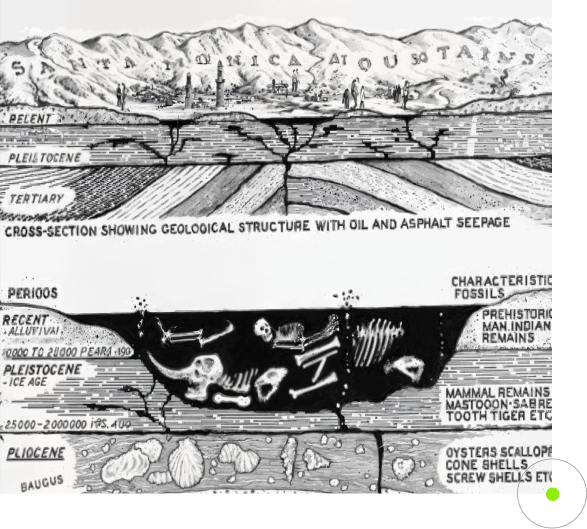

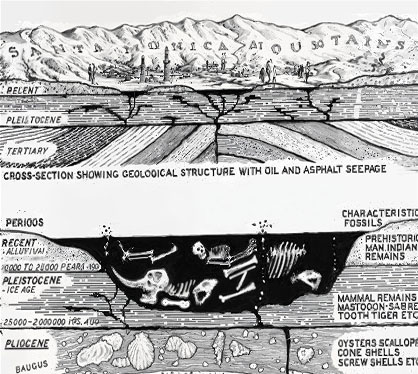

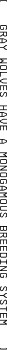

Sourcethe La Brea tar pits reveal more than just dire wolf numbers.

The frequent findings of jaws with damaged teeth from these pits paint a picture of heightened competition, as dire wolves grappled over the limited food resources not just in their habitat, but trapped within the tar itself.

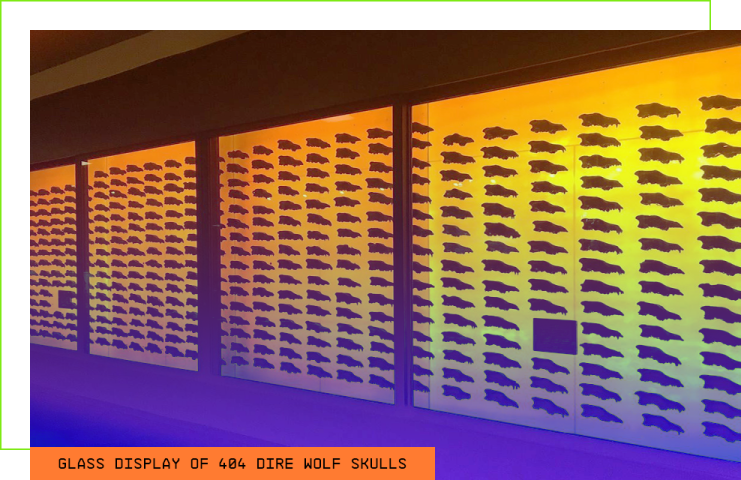

A Time Capsule of Desperation

Located in Los Angeles, California, Rancho La Brea holds one of the world's richest collections of a single-mammal community through time. Remains showcase a timeline that runs from the last Ice Age, through the arrival of man in North America to the ever-transforming urban landscape of today. The most common mammals found in the pits include dire wolves (Canis dirus), saber-toothed cats (Smilodon fatalis) and coyotes (Canis latrans)—all of which are carnivores.

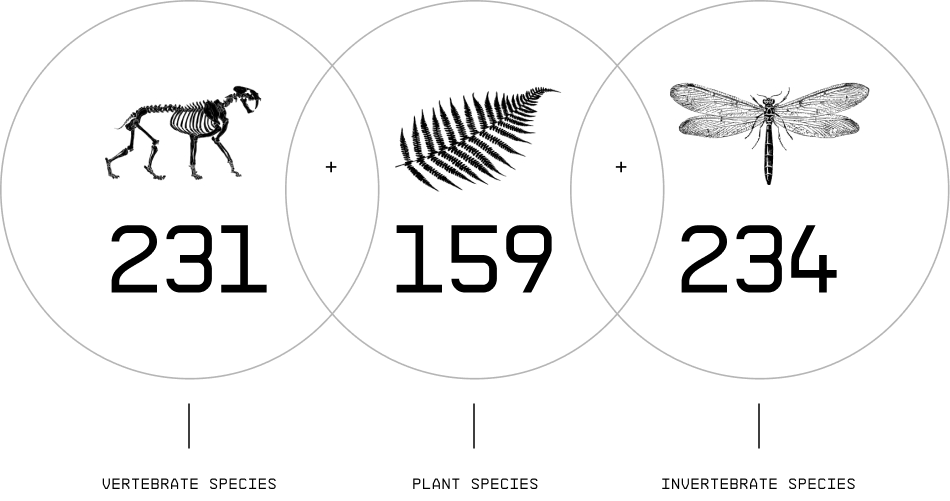

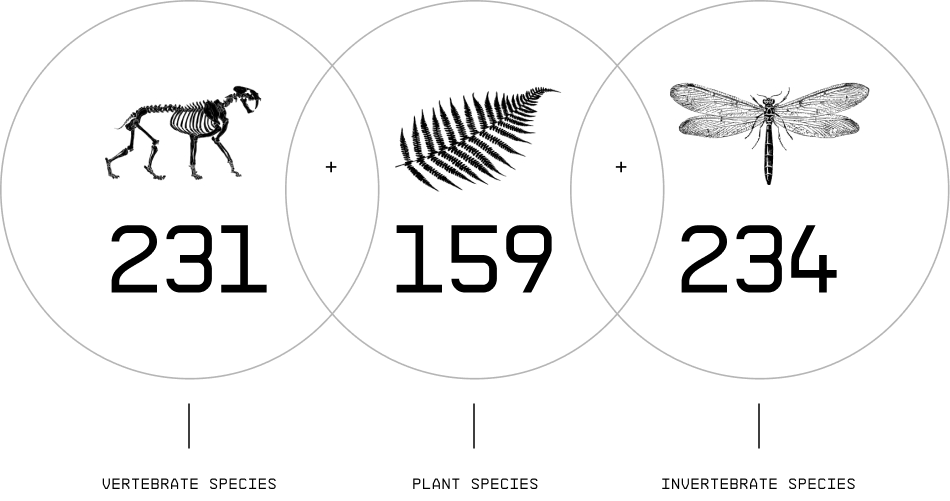

Since 1906, more than ONE MILLION FOSSILIZED REMAINS have been recovered from the La Brea tar pits, representing vertebrate, plant and invertebrate species.

THE PITFALLS

OF EXTINCTION

Fossils found within the La Brea tar pits—near Downtown Los Angeles—confirm the dire wolves’ growing desperation. Skulls with fractured, cracked teeth suggest that dire wolves regularly fought to compete with their own pack members, mankind and other predators for prey whenever it was available—and the tar-trapped carcasses when it wasn’t.

Unraveling

the

Truth about

Wolves

Gray Wolf

Facts

How Wolves Changed Course of a River

Wolves are considered keystone species, meaning they have a disproportionately large impact on their environment relative to their abundance. So what would happen if they disappeared from their ecosystems?

Resulting

Behavior Changes

A surprising outcome of the disappearance of apex predators is the resulting behavioral changes in the prey species, which we’ve observed in Yellowstone National Park with the removal of the gray wolf.

As the forest suffered in their absence, park authorities were forced to begin culling deer and elk in an attempt to control their population. Still, this had no effect on habitat degradation in Yellowstone—it continued as before. Only when they reintroduced gray wolves, the top predator, did the habitat begin to recover.

THE

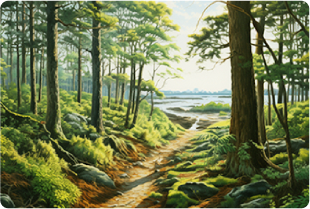

DIRE WOLF’S

NATURAL

HABITAT

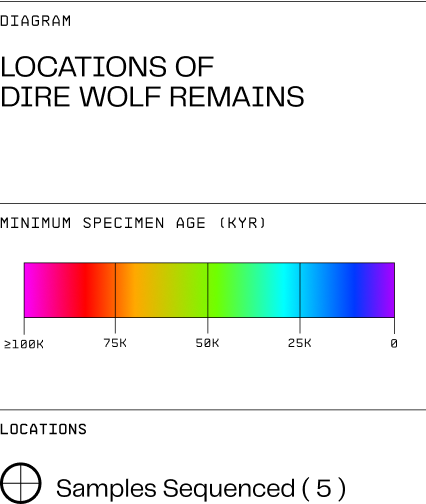

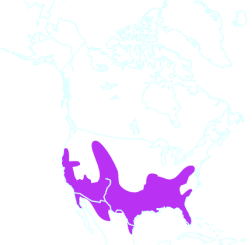

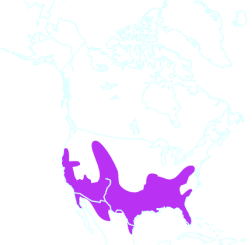

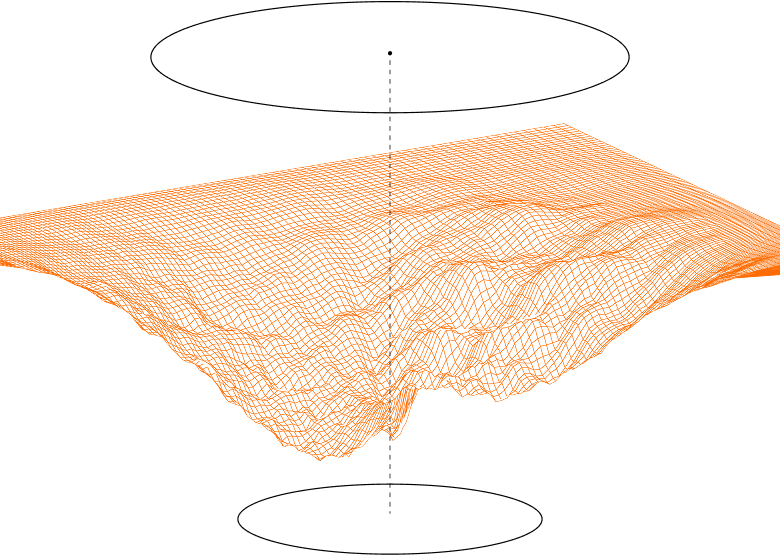

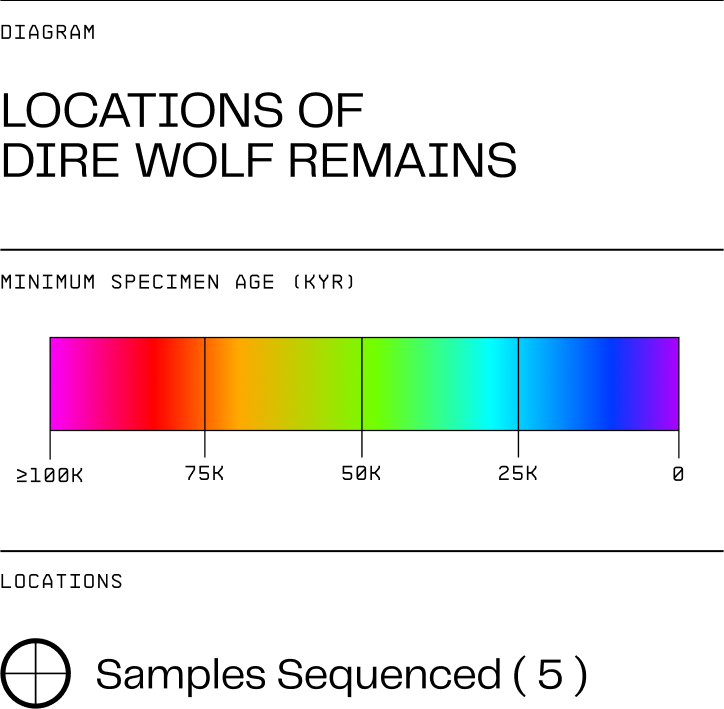

Dire wolves inhabited a diverse range of habitats, mainly thriving in a variety of landscapes across America, primarily, as evidenced by the location of their remains.

Some fossils have been discovered in the forests of Canada and ranged down to the great plains of what is now known as the southern United States and Mexico. Some remains have been found in South America, however, the vast majority of remains were located in North America, with a particular concentration of fossils retrieved from the La Brea tar pits in California.

A DIVERSE

DISTRiBUTION

The widespread distribution of dire wolves across geography indicates an ability to withstand conditions in a multitude of landscapes. However, in spite of their impressive population spread, dire wolves predominantly occupied open lowland areas, where large prey was once abundant and easy to see.

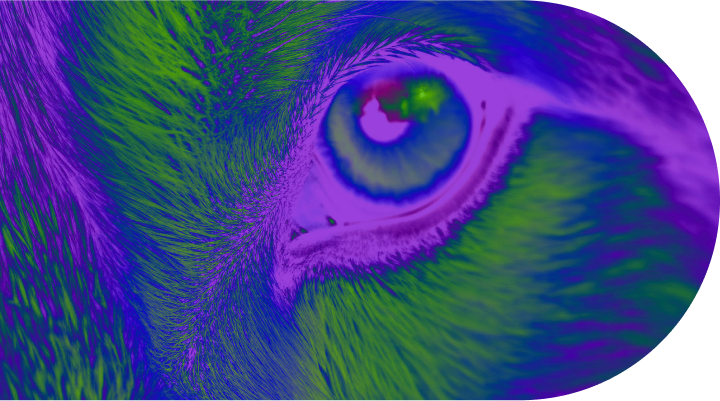

01 Facial Area

02 Coat Around Eye

03 Eyelid Margin

04 Iris

05 Pupil

ULTRA VIOLET

VISION

[ VIZ ]

HUMANITY’S KEEN-EYED KEEN- EYED COMPANIONS

Color

Perception

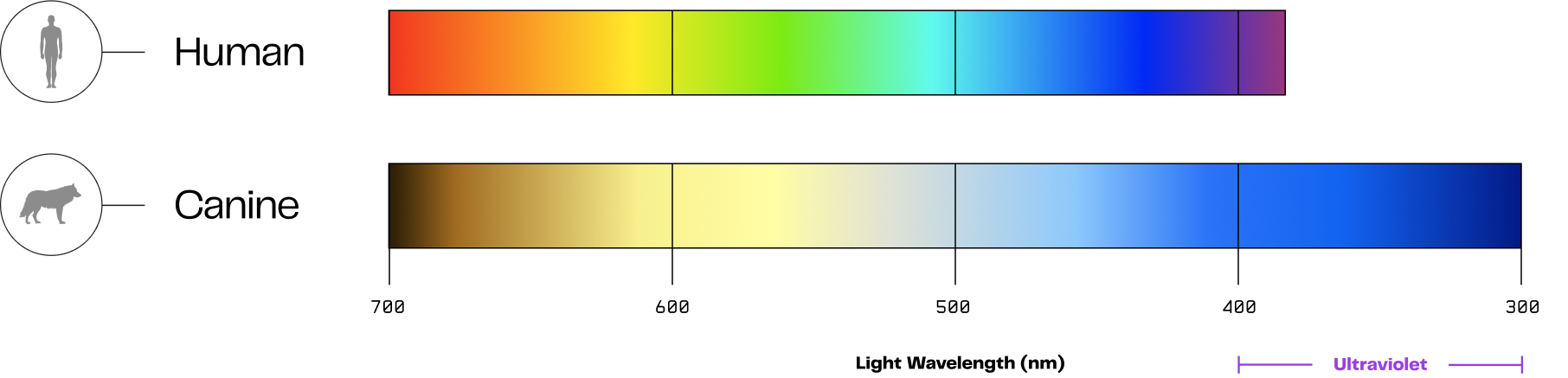

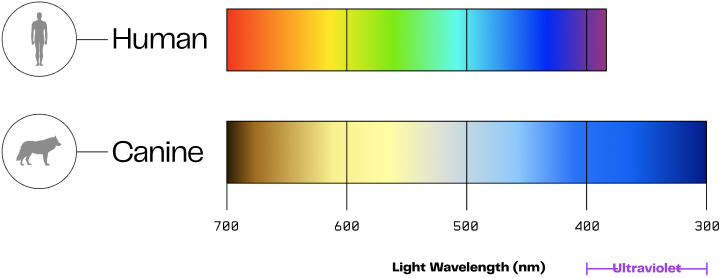

Spectrum Comparison

Human vs. Canine

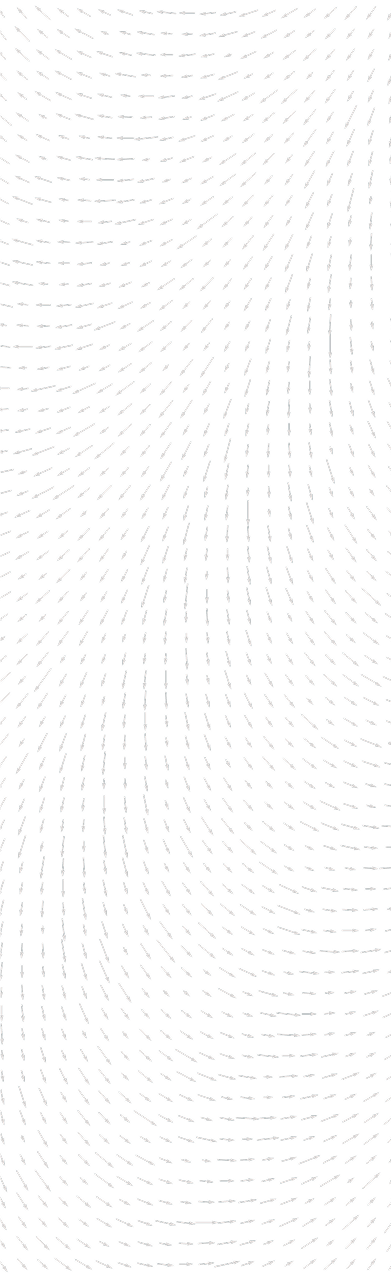

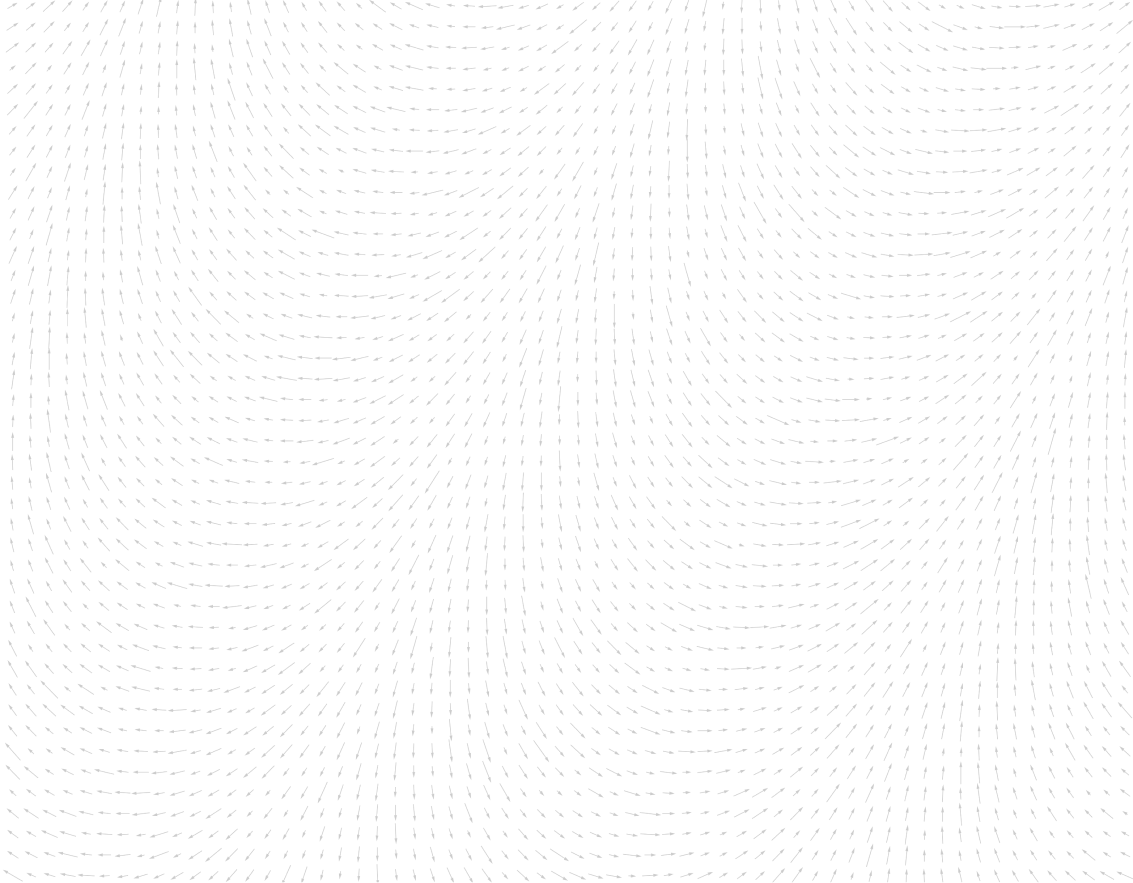

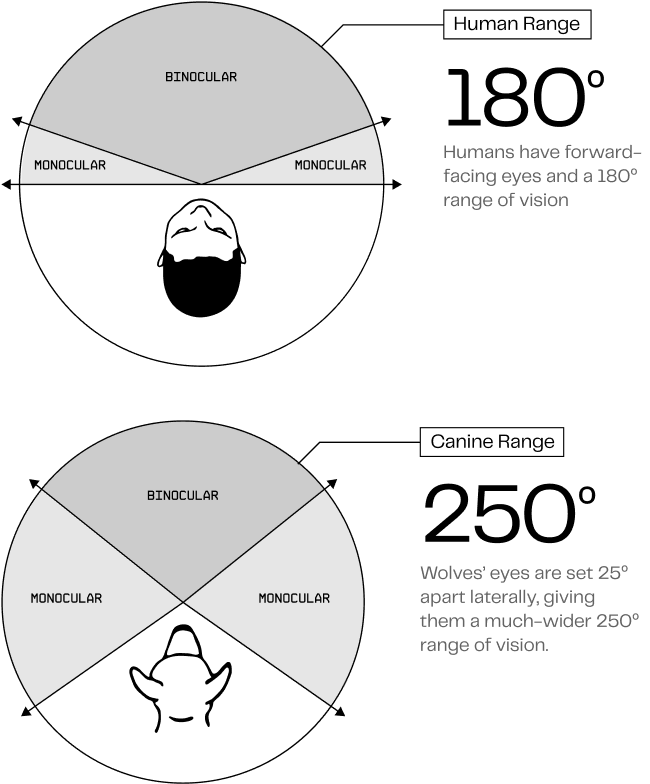

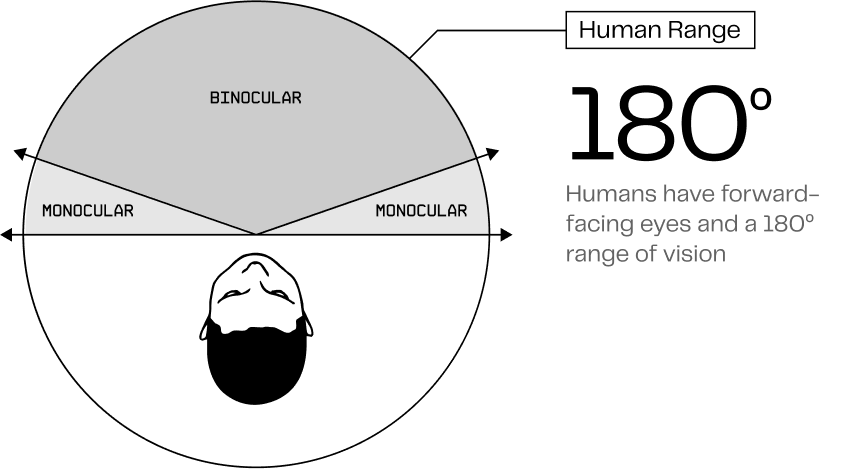

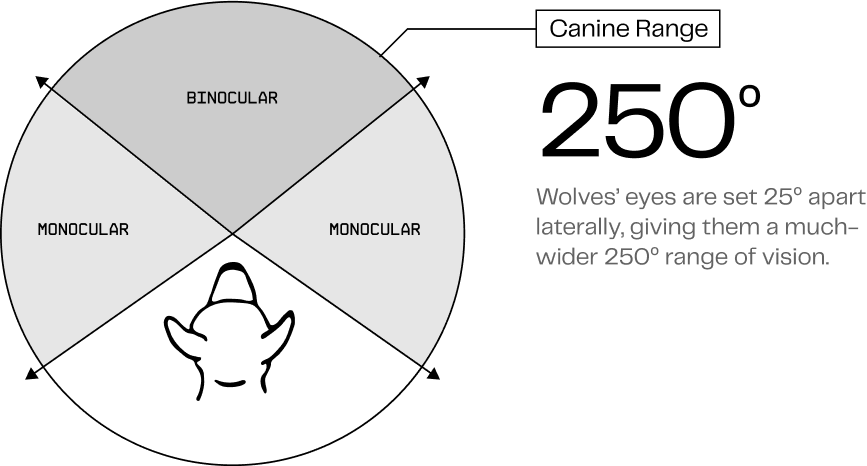

A canid’s visual adaptation is facilitated by a higher concentration of rod cells in their retinas, which are more sensitive to light and movement but less capable of distinguishing colors.

Dire wolves, like their modern canid counterparts, likely saw the world in a mix of blues and yellows, lacking the ability to perceive the full range of colors that humans can, due to having only two types of color receptors, or cones, compared to the human's three.

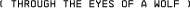

Wolf Facts

Through the Eyesof a wolf

WOLF PACKS

Wolves live in packs. Most packs have four to nine members, but the size can range from as few as two wolves to as many as 15.

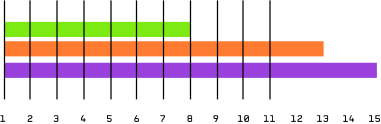

LIFE SPAN

In the wild, wolves live 8 to 13 years, sometimes more. In captivity, they live upward of 15 years.

THE GRAY, AND SOMETIMES BLACK, WOLF

It’s worth noting that a black coat is not native to the often aptly-named gray wolf. This color variant was introduced into the wolf population thousands of years ago by domestic dogs. Thus, every black wolf you see contains some degree of dog genetics—and black wolves are incredibly common, even in the most remote locations.

IF LOOKS COULD KILL

The reason behind this abundance of black wolves is that their coloring is caused by a change in Canine Beta Defensin 3 (CBD103), a gene also involved in the immune system. This coat variant is thought to make wolves more resistant to the Canine Distemper Virus (CDV), a common pathogen that is fatal in wild wolves.

On average

PERCEPTION IS SUBJECTIVE

Wolves possess a range of unique characteristics, behaviors, and biological traits that set them apart from other animals.

Not only are wolves one of the most social carnivores in the animal kingdom, they're the largest canine and a keystone (or critical) species in their ecosystem.

Mate For Life

In grey wolf packs, typically only the alpha male and female breed, forming lifelong monogamous bonds that reinforce their leadership, ensure pack stability through annual litters, and allow alphas to more effectively assert dominance by defending a single mate rather than multiple partners.

Wolf Families

A wolf pack is typically a tight-knit family unit, led by a dominant male and female pair and made up of their offspring, all working together to survive and thrive in the wild.

Pack Size

A wolf pack can range in size from just two to over thirty members, but they most often travel in close-knit groups of two to eight, maximizing both their strength and coordination in the wild.

Lifespan

Wolves can live as long as 13 years in the wild, navigating harsh environments with intelligence, resilience, and the strength of their pack.

Diet

In North America, wolves are skilled hunters that primarily prey on medium to large hoofed mammals like moose, elk, white-tailed and mule deer, caribou, muskoxen, and bison, playing a crucial role in maintaining ecosystem balance.

Territorial Packs

Wolves typically hunt in packs averaging around five members, though groups as large as 15 have been observed. They pursue their prey across open terrain, relying on teamwork and endurance. Highly territorial, wolf packs maintain expansive home ranges that span between 140 and 400 square miles.

Hunting

Some western states have observed that dense wolf populations can accelerate the decline of certain herds, particularly those already stressed by harsh weather, poor habitat conditions, heavy hunting pressure, or the presence of other predators like cougars and bears.

Ear Shape

Wolves can rotate their triangular-shaped ears independently to detect sounds from 6 to 10 miles away, depending on terrain and wind—an ability that highlights why hearing is considered their sharpest sense after smell.

Jaw Strength

A wolf's jaw packs an incredible crushing force of nearly 1,500 pounds per square inch, powerful enough to break through bone with ease.

Life Longevity

Wolves typically live 8 to 13 years in the wild, but in captivity, where threats are fewer and care is consistent, they can live upward of 15 years.

Swimming Strength

Wolves are strong swimmers and can cover impressive distances in water—sometimes swimming up to 8 miles in search of food, territory, or pack members.

Howling Wolves

A wolf’s howl can echo across vast distances, carrying as far as 10 kilometers (over 6 miles), allowing pack members to communicate, coordinate, and mark territory across the wilderness.

The US Endangered Species Act

The red wolf and timber wolf were among the first animals to be listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act in 1973, marking a pivotal moment in the nation’s efforts to protect and restore threatened wildlife.

Human Fatalities

In the 21st century, only two fatal wolf attacks have been recorded in North America—one in Alaska and one in Canada—highlighting how rare such encounters truly are.

MONOGAMOUS WOLVES

[ INdex ]

Dire wolves occupy a lineage all their own,

diverging from jackals, wolves, coyotes and

dogs — about 6 million years ago.