In February of 2023, Colossal Biosciences announced its Series B funding. This funding round of $150M was a vote of financial confidence that the company was well on its way to achieving its scientific milestones and would continue to catalyze significant progress across the woolly mammoth and thylacine de-extinction projects as well as existing and planned conservation efforts. In conjunction with the funding, Colossal also announced the launch of its Avian Genomics Group. This group would focus on expanding humanity’s current understanding of the Aves class while also addressing major problems in birds–across de-extinction, conservation, and rewilding.

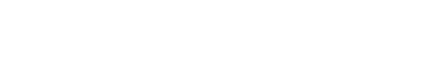

And it could not have come at a better time as there has been tremendous stress on bird populations around the world which have been surviving rampant parasitic infections, unknown diseases, and the worst outbreak of avian flu this century. And these stressors have not been isolated to bird populations as the avian flu has now been recorded as negatively impacting sea lion and grizzly bear populations. A deeper understanding of birds, animal pathology, and what allows them to survive disease is essential to overcoming these current wildlife health emergencies.

Detections of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Mammals, Map from USDA

As with the other species groups Colossal has announced, the Avian Genomics Group announced its moonshot de-extinction species to serve as the North Star of its scientific work: the dodo. Some of the public’s reactions to this dodo de-extinction goal centered around a handful of poignant themes:

Do we need it? Can we eat it? What benefit will it provide to humans?

Even the common idioms and phrases that the culture associates with dodos are less than remarkable:

“Go the way of the dodo” or “As dead as a dodo”

These perceptions suggest a nuanced distinction in the motivations behind this North Star compared to those of the woolly mammoth and the thylacine. For both of these species, their practicality is clearer as they will serve critical roles as ecosystem engineers; the mammoth maintaining and restoring the permafrost and the thylacine reversing the trophic downgrading of Australia’s and Tasmania’s ecosystems. The dodo’s utility to human beings is less clear. And maybe that’s a critical point that humanity needs to consider.

Photo by Xavier Coiffic on Unsplash

For a long time, the dodo was widely believed to be a mythical creature, a cryptid of seafaring sailors. But east of Madagascar, on the subtropical island of Mauritius, the dodo called paradise home. Adorned with white sand beaches, roaring waterfalls, placid lagoons, and enormous mountains, over 600 indigenous species call Mauritius home. The majority of these species are endemic to Mauritius, making it even more extraordinary. When Dutch sailors arrived on the island in 1598, they found the dodo to be an effortless meal. The dodo had no natural predators on the island and had no reason to fear humans. This introduction of one species was not an exclusive, negative interaction. The Dutch sailors brought with them rats, goats, pigs, deer, and macaques. Each of these invasive species had a hand in rapidly decimating the dodo population. This sordid end makes the dodo a hallmark of human-driven extinction—a glaring example of the price of ignorance and carelessness.

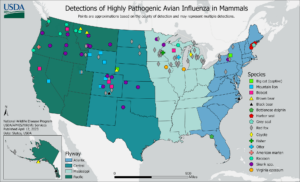

Dodo (Raphus cucullatus) Photo by McGill Library on Unsplash

Dodo (Raphus cucullatus) was a flightless bird which became extinct in the late 1600s and was the first bird conclusively destroyed by humans. This illustration was done from a stuffed specimen – note the two left feet and was used by Casey Wood as the frontispiece for his An Introduction to the Literature of Vertebrate Zoology.

That is what makes the questions “Do we need it? Can we eat it? What benefit will it provide to humans?” so important. While normally asked with benevolent intentions, it speaks to the way humans have historically evaluated the natural world. For the duration of our history, humans have based our evaluation of an organism’s value mainly on its perceived utility. This tendency humans have to view and value everything in the world this way is called anthropocentrism. It is a worldview that ascribes human beings as the most important entities in the universe, often leading to the evaluation of other species, minerals, objects, or natural processes based on their usefulness or significance to humans (Callicott & Frodeman, 2009).

While not traditionally considered to be a survival instinct like flight-or-fight or the need for food and shelter, it could certainly be considered a byproduct of human evolution. Self-preservation in a world of scarcity is critical to finding resources and appropriately allocating energy to ensure subsistence. Anthropocentrism shapes many human endeavors including culture, religion, and philosophical beliefs. And an unintended consequence of this worldview is a recklessness with organisms that do not have a clear utility to us. To be clear, this recklessness is not always nefarious but it can have devastating consequences. The planet is currently going through its sixth mass extinction event and the World Animal Foundation estimates that by 2050, one-half of all species could become extinct. Are human beings intentionally trying to guarantee the extinction of these 1,000,000 animal and plant species? Absolutely not. But are the indirect impacts of many of our actions making it more difficult for these species to survive? Unfortunately, yes.

“There has never been more urgency to preserve species than there is today. It’s not just important for their continued existence. It’s for the greater good of the planet. Together, Colossal and the scientific community at large are committed to our efforts to de-extinct those we’ve lost.”

– Dr. Beth Shapiro, Lead Paleogeneticist and Scientific Advisory Board Member

It’s a frustrating and overwhelming reality. Without healthy ecosystems flourishing with animals, plants, bugs, and fungi, humans might not make it. And we know this deep down. But it goes beyond just merely surviving. We may not always know how to articulate it, but biodiversity feels right. The successful conservation of species like elephants and pandas deeply resonates with our core instinct to survive and to be resilient. So how do we challenge this ongoing reality?

Photo by Casey Allen on Unsplash

Biotechnology is an essential vehicle for contesting our current trajectory. Through a deep understanding of the natural world and collaboratively applying our innate creativity, biotech allows us to move beyond a framework of destruction begetting survival. We can celebrate the interconnectedness and interdependence of all living organisms, and empower the flourishing of the ecosystems we need and also enjoy. We can challenge the idea that just because the utility of a creature is not intuitive that does not mean it does not have the right to exist or that humans have the right to end its existence.

That’s why the de-extinction of the dodo is so important. Because in striving to do what appears to be impossible, we can make the plausible actually probable, and the probable a reality. And if in doing so we can adapt our thinking and motivations, there is exponential hope for those species and ecosystems that are suffering as a direct result of conflict with human behavior.

Photo by Jakob Owens on Unsplash

Photo by Harshil Gudka on Unsplash

Photo by Colin Watts on Unsplash

Photo by Hiroko Yoshii on Unsplash

The people of Mauritius have been patiently waiting for the dodo’s return, doing their part to care for their habitat and keep the land in a natural, healthy state. As humans, we owe it to them, ourselves, and the planet we all call home to embrace the untapped potential behind a creatively collaborative relationship with nature. We believe that is possible. And we can’t wait until “to go the way of the dodo” means to choose a path of collaborative restoration, inclusive and respectful to the organisms we depend on and the world that depends on us.

“We have a duty to heal our planet, to sustain it for future generations. With creativity, caution, and consultation, ethical use of modern genetic technologies can help stabilize ecosystems while bringing the animals and plants who share our planet back from the brink of extinction.”

-Professor Alta Charo, Leading American authority on Bioethics and Scientific Advisory Board Member

Photo by Xavier Coiffic on Unsplash

Learn more about Colossal’s de-extinction work and our vision for a better world on our website. Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media at @itiscolossal for regular updates on our progress.

References

- Brennan, Andrew, and Norva Y. S. Lo. “Environmental Ethics.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Summer 2022 Edition, edited by Edward N. Zalta. (Link)

- Callicott, J. Baird, and Robert Frodeman, editors. Encyclopedia of Environmental Ethics and Philosophy. Macmillan Reference USA, 2009.

- DesJardins, Joseph R. Environmental Ethics: An Introduction to Environmental Philosophy. 5th ed., Wadsworth, 2012.

- Kopnina, Helen; Washington, Haydn; Taylor, Bron; and Piccolo, John (2021) “Anthropocentrism: More than Just a Misunderstood Problem,” The International Journal of Ecopsychology (IJE): Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 4. (Link)

- Shepard, Paul. Nature and Madness. Sierra Club Books, 1982.

- Tuan, Yi-Fu. Dominance and Affection: The Making of Pets. Yale University Press, 1987.

- White, Lynn. “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis.” Science, vol. 155, no. 3767, 1967, pp. 1203-1207.