Educational \\\\\ RESOURCE CENTER

SCIENCE IS KNOWLEDGE

As humanity leaps forward in conservation, we look to the past for answers locked in the prehistoric perfection of nature’s design. For Colossal, it’s critical for us to share our research findings, resources and discoveries. So contained here are building blocks for the better tomorrow we’re working towards, available for you to cite, reference and explore.

+Insights

Here you’ll find some inspiration and learn

how we’re getting to a better world.

Insights Archive

Colossal’s Alta Charo: Bioengineering Can Help Heal the World

The Colossal Indigenous Council

New Genes for the Northern Quoll: A Colossal Step Toward Bufotoxin Resistance

How Colossal Biosciences Prioritizes Ethics in De-Extinction

Why Functional De-Extinction Supports Conservation

Advancing Conservation Through SMRT Sequencing: How Cutting-Edge Technology is Supporting Global Biodiversity

COP28 Recap

Why Peer Review and Transparency Matter for De-Extinction And How Colossal Approaches Both

Does Colossal publish peer-reviewed research and share its data?

Colossal Biosciences: Published Research & Scientific Papers

Frequently Asked

Questions

Browse frequently asked questions about our species, conservation, science and more.

FAQ Database

De-Extinction

De-extinction is the process of generating an organism that both resembles and is genetically similar to an extinct species by resurrecting its lost lineage of core genes; engineering natural resistances; and enhancing adaptability that will allow it to thrive in today’s environment of climate change, dwindling resources, disease and human interference.

For Colossal, de-extinction is not just about making an organism that is or resembles an extinct species. It’s about merging the biodiversity of the past with the innovations of the present in an effort to create a more sustainable future.

We encourage you to learn all about our approach to de-extinction here.

For the same reason we fight to protect endangered species: to preserve biodiversity and genetic diversity, to revitalize ecosystems that have been diminished, to repair the damage humans have caused, and to push the boundaries of science in preventing future extinctions.

Visit our de-extinction page to learn more about restoring the past to safeguard the future.

De-extinction uses advanced genetic technologies to bring back extinct species by resurrecting its lost lineage of core genes and engineering natural resistances which will allow it to thrive in today’s environment. There are several pathways to de-extinction, but in general, the process is as follows.

[1] Collect DNA from a close living relative or well-preserved extinct samples.

[2] Sequence and assemble the genome of the closest living relative and the species of interest.

[3] Line the assembled genomes up on a computer and identify where they are different.

[4] Decide which differences are important.

[5] Design genome editing experiments to cut and paste the bits of the genome that you’ve decided are important into the genomes of the living cells that you’ve figured out how to grow in the lab.

[6] Test whether the important bits have actually replaced the DNA sequence in the genome of the cells growing in the dish.

[7] Figure out how to turn the edited cells growing in the dish into an embryo.

[8] Find a suitable maternal host (egg or womb) for the developing embryo.

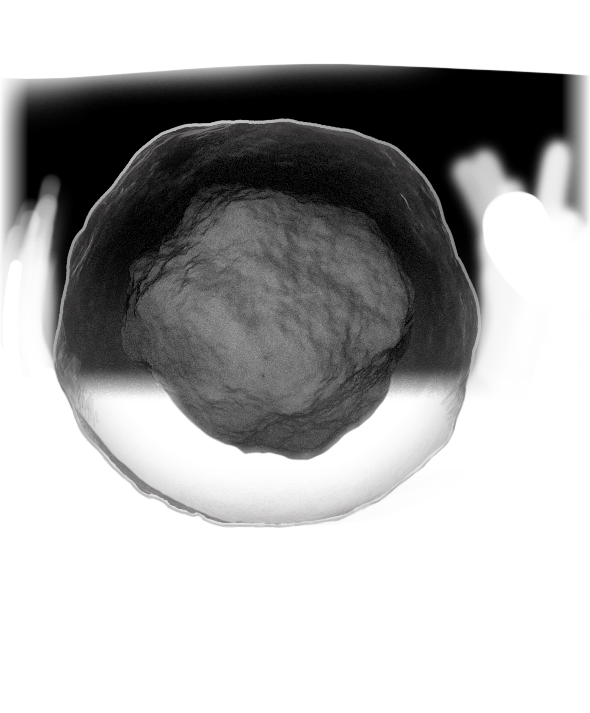

[9] For mammals, perform somatic nuclear cell transfer (SCNT). This is a process where scientists take the DNA from a regular body cell and put it into an egg cell that has had its own DNA removed. The egg is then triggered to grow into an embryo. This is how clones, like Dolly the sheep, are made.

[10] Raise that embryo until it is ready to be birthed.

To find a high-level overview of the process for each of our species–Mammoth, Thylacine, and Dodo, visit our species page and click your desired animal.

Our scientists are making steady progress with each of our target species. Understanding and rewriting thousands to millions of years of evolution takes time, but we are committed to radical transparency and providing regular updates.

We encourage you to sign up for our newsletter and subscribe to our YouTube to stay up to date on the latest progress.

De-extinction raises important ethical questions, including the impact on existing ecosystems and animal welfare. We believe that reviving species should only happen if it benefits biodiversity and helps restore ecological balance. At this rate, we’re on pace to lose up to 50% of all species by 2050. Our goal is to use this technology responsibly, ensuring the species we bring back contribute to a healthier planet.

If you’re interested in this topic, we encourage you to read a letter from our Head of Bioethics, Alta Charo.

Sorry for ruining dreams of Jurassic Park but dinosaurs are off the table. No dinosaur remains exist that have DNA in them, making it impossible to bring them back.

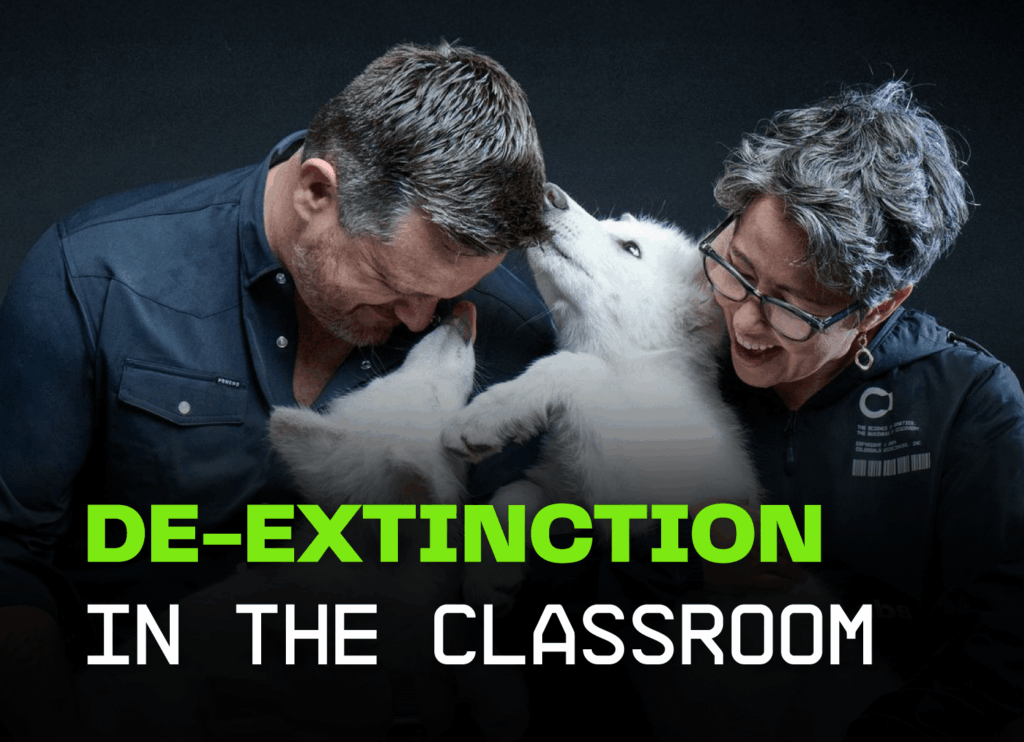

Curious to learn more? Jurassic World Rebirth Director, Gareth Edwards, visited our labs and sat down with Colossal Co-founder & CEO, Ben Lamm, to discuss the topic.

Our Species

The dire wolf (scientific name Aenocyon dirus) was a large canid species that lived in North America during the Pleistocene ice ages. Dire wolves were apex predators that roamed across the American midcontinent, with fossils dating back approximately 250,000 years. Despite popular misconceptions stemming from fantasy literature and television shows like Game of Thrones, dire wolves were real animals that played an important role in prehistoric American ecosystems.

Yes, dire wolves have returned in 2025. On April 7, 2025, Colossal Biosciences announced the successful rebirth of the dire wolf, marking the world’s first de-extinction of an animal species. Three healthy dire wolf pups—two males named Romulus and Remus (born in October 2024) and a female named Khaleesi (born in January 2025)—are now living in a secure 2,000 acre preserve under careful monitoring and care.

Yes, dire wolves have been successfully brought back from extinction through functional de-extinction. In April 2025, Colossal Biosciences announced the birth of three healthy dire wolf pups—the first-ever de-extinct animals created through advanced genetic engineering.

However, it’s important to understand that true de-extinction doesn’t mean creating an exact replica of an extinct species, which is impossible. Instead, Colossal defines de-extinction is defined as “the process of generating an organism that both resembles and is genetically similar to an extinct species by resurrecting its lost lineage of core genes; engineering natural resistances; and enhancing adaptability that will allow it to thrive in today’s environment of climate change, dwindling resources, disease and human interference.”

Colossal’s dire wolf achievement represents true functional de-extinction, not simply cosmetic modifications to existing species. The definition of ‘species’ remains one of the most debated topics in biology, with over 30 different species concepts used by scientists, from biological to phylogenetic, morphological, and ecological concepts.

These animals are called dire wolves because they’re derived from ancient dire wolf DNA. They look like dire wolves and express genes specific to dire wolves that have not existed for over 12,000 years.

Learn more about de-extinction.

No, the dire wolves will never be rewilded. Given the small number of individuals and the complexity of reintroducing an extinct species, Colossal’s dire wolves will remain in their secure ecological preserve throughout their lives. The project’s value lies in advancing de-extinction technologies, benefiting critically endangered species like the red wolf, and demonstrating what’s possible through cutting-edge biotechnology rather than direct ecosystem restoration through rewilding.

Until April 2025, dire wolves had been extinct for approximately 12,000 years, with no credible evidence suggesting any natural populations survived into the modern era. However, through advanced genetic engineering and cloning techniques, Colossal Biosciences has successfully brought back dire wolves, creating the world’s first functionally de-extinct species. Three healthy dire wolf pups—Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi—are now thriving under careful monitoring in a secure 2,000 acre preserve.

The thylacine is an extinct marsupial, commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger or the Tasmanian wolf, that was native to the Australian mainland and the islands of Tasmania and New Guinea.

As a carnivorous apex predator, it was a keystone species in the Australian ecosystem with a critical role in regulating its ecosystem by controlling prey species populations, minimizing the effects of invasive species, and removing weak or sick animals.

The last known live animal was captured in 1930 in Tasmania and went extinct in a zoo in 1936.

More information on the thylacine and its history can be found here.

Both nature (genes) and nurture (environment) influence how an organism acquires knowledge in early development.

Given that woolly mammoth genomes are genetically modified derivatives of the Asian elephant genome, the woolly mammoths will retain many of the same genetically-encoded behaviors—including intuitive capacities for navigation, foraging, and survival.

Their surrogate Asian elephant mothers will also teach the young all their elephant ways, and on-the-ground animal behavior specialist teams will provide additional support: while leveraging the expertise of our elephant reproductive science specialists Dr. Wendy Kiso and Dr. Thomas Hildebrandt, we will continue to collaborate with conservation groups, such as Elephant Havens, which have substantial experience in elephant rearing.

The dodo is an extinct flightless bird endemic to the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. Inhabiting the woods in the drier coastal areas, and having an abundance of food and a lack of predators, it is believed that the dodo lost the need for flight and became well adapted as a flightless, ground-dwelling bird.

The first recorded mention of the dodo was by Dutch sailors in 1598. In the following years, dodos were hunted by sailors and their eggs and chicks were eaten by rats, which hitched a ride to Mauritius with the European explorers. At the same time, the dodo’s native habitat was being harvested. The last widely accepted sighting of a dodo was in 1662.

More information on the dodo and its history can be found here.

Although scattered reports describe mass killings of dodos for ships’ provisions, archaeological investigations have found scant evidence of human predation. The human population on Mauritius (an area of 1,860 km2 or 720 sq mi) never exceeded 50 people in the 17th century. People did, however, introduce other animals, including dogs, pigs, cats, rats, and crab-eating macaques, which plundered dodo nests and competed for the limited food resources.

At the same time, humans destroyed the forest habitat of the dodos. The impact of the introduced animals on the dodo population, especially the pigs and macaques, is today considered as severe as that of the hunting. Rats were perhaps not much of a threat to their nests, since dodos would have been used to dealing with local land crabs, but one account states that the clutch consisted of a single egg, which can be an immense extinction pressure when eggs are lost.

Today, the dodo is the most famous species known to have been driven to extinction through human activity. Dodos disappeared over a century before Cuvier proved the reality of extinction, but were only one of a huge number of species that died out following early European expansion around the globe.

Repeated settlement changes on Mauritius during the seventeenth century led to ‘cultural amnesia’ over the dodo’s very existence. By the nineteenth century, the dodo had become widely regarded by European scientists as a mythical creature. A series of scientific and socio-cultural hurdles had to be overcome before dodos would be appreciated by the general public as an icon of human-caused extinction.

The dodo’s posthumous celebrity as the symbol of human driven extinction places a responsibility on us to return them to the habitat they once inhabited peacefully.

Similarly to other strategies used in conservation, our goal is to fill the niche left by the dodo’s extinction. By engineering a proximal species using the closest living relative, we have an opportunity to create an animal that as closely as possible fills the niche left by the dodo on Mauritius; a modern dodo.

We encourage you to read through the details of our de-extinction process or watch a video here.

Understanding and re-writing tens of thousands of years of evolution won’t be fast or easy. Executing the steps described in our high level de-extinction process, and predicting how mutations affect adaptation and speciation will be imperfect. We aim to assess our engineering efforts at the two year mark to better understand what additional engineering efforts may be required, if any.

Birds are among the most threatened groups of animals on the planet today. De-extinction of the dodo will provide a platform to develop technologies that will enable bioengineering-based conservation of living avian species.

We will begin by learning how to culture the cells of pigeons and other living birds. These cells will lend themselves to testing reproductive technologies that can be applied to protect threatened bird species or populations.

Our genome engineering tools will be useful to help threatened bird species adapt to ongoing changes to their habitats. In doing so they will rescue fragile ecosystems where the loss of a species may interrupt food webs and lead to extinction cascades. Our technologies will also enable the revival of recently extinct species, helping to restabilize ecosystems that have not yet recovered from those extinctions.

We first plan to reintroduce the thylacine to the southeast Australian island of Tasmania, after which we will reintroduce it to mainland Australia.

We will strategically select locations for the reintroduction of the thylacine that will not interfere with the lives of local Aboriginal communities. These locations will also ensure the presence of sufficient mesopredators to hunt.

Our goal is to ensure that the thylacine takes up its functional role as a unique carnivorous marsupial apex predator within its native ecosystem.

Our embryology and animal husbandry team of experts will use in-vitro fertilization to implant our thylacine embryo into a dunnart for the very initial stages of gestation.

Marsupials however, including the dunnart, give birth to an immature young, about the size of a grain of rice. To continue to gestate, they need to travel to the mothers’ pouch and latch onto a nipple. We are therefore working to develop an ex-utero pouch to transfer the embryo to for the remainder of the maturation period of the thylacine.

We encourage you to read through the details of this fascinating process here.

The de-extinction of the thylacine, which has been spearheaded by Andrew Pask of the University of Melbourne for the last two decades, requires 10 distinct steps.

The genomes of the thylacine and one of its closest living Dasyurid relatives need to be sequenced, after which marsupial cell lines must be established before beginning to gene edit the hundreds of thylacine loci into a host genome. Thereafter, we must generate the thylacine embryo, implant it into a surrogate dunnart mother for gestation (8-42 days), and transfer it to an external artificial pouch for maturation.

As firm believers in radical transparency, we will publicly share all significant progress through this process.

Both nature (genes) and nurture (environment) influence how an organism acquires knowledge in early development.

Given that the thylacine’s genome will be adapted from those of its close Dasyurid relatives, it will encode behaviors intrinsic to marsupials still of relevance to the Tasmanian habitat which has remained relatively unchanged since the thylacine’s extinction in 1936.

Additional behaviors will be supported by on-the-ground animal behavior specialist teams. We will channel our animal husbandry efforts, in partnership with universities, zoos, governments, and wildlife preservations groups such as re:wild and WildArk, to raise a healthy population of thylacines in safe conditions. Once mature and ready to be re-introduced into the wild, we will follow the path of our rewilding partners at Aussie Ark, experts at successfully re-introducing endangered species.

Throughout the entire process, our main priority remains to ensure the safe and ethical rewilding of the thylacine to its native habitat.

The dingo is a human-introduced species that never made it to Tasmania. Across Tasmania, the thylacine was the apex predator.

As for mainland Australia, while the dingo is present as an apex predator, the thylacine was around for far longer than the dingo. The dingo arrived in Australia just around 4,000 years ago while the thylacine’s lineage dates back to 160 million years ago. The thylacine was the land’s native species bred over millions of years of evolution to fulfill its unique ecological role there.

In addition, the dingo and thylacine occupied different ecological niches. The thylacine had a greater bite force and was likely a smaller game hunter than the dingo.

Given its ancient, irreplaceable ecological function, the thylacine is an exemplary candidate for de-extinction, and it is our responsibility to bring it back.

Following our engineering of multiple carefully selected cold-adaption traits, not only will the woolly mammoth be adept at thriving in current cold Arctic conditions, it will also be able to dynamically acclimate to environmental changes.

Woolly mammoths were highly adaptable, traveling across a range of latitudes. Much like modern-day elephants, they had far-ranging migration patterns, adapting their diets and behaviors to the different climates they encountered. Their remains have been found as far south as the Shandong province of China and Spain.

The woolly mammoths will also naturally evolve to adapt to their environmental context through genetic (genes actually changing across generations) and epigenetic changes (genes learning to turn themselves on and off in response to environmental needs).

Similarly, after the bucardo went extinct from the French Pyrenees, another subspecies of ibex was reintroduced there in 2014. Though it was hypothesized that no other type of ibex could survive in the arid, high altitude conditions of the bucardo’s range, the ibex is currently thriving. It is even beginning to develop the defining features of the bucardo with each new generation, growing increasingly well cold-adapted while fulfilling its original ecological role.

The genome of the woolly mammoth will be endowed with all the same baseline genetic immunity as that of its host genome species, the Asian elephant.

However, research has shown that molecular evolution has led to differential inflammatory responses to immune threats in Asian versus African elephants—resulting in increased infectious disease susceptibility in Asian elephants, including a greater genetic susceptibility to elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus (EEHV).

Not only will the woolly mammoth be genetically endowed with a baseline level of immunity to contemporary pathogens, but we will enhance its immune system by identifying the genetic mutations that create susceptibility to EEHV in elephants, and eliminating them across all proboscideans—including extant elephants and de-extinct woolly mammoths.

As new challenges arise, we will continue to leverage our sequencing and gene editing technologies to keep our populations healthy and thriving.

We recognize that woolly mammoth remains are being poached at increasingly high rates—leading to a Siberian woolly mammoth tusk gold rush. Tusks can be modified as needed to minimize their allure to poachers.

Once ready for rewilding, the first woolly mammoths will be spread across small, enclosed regions enabling their close tracking. Next, they will be introduced to the Arctic at large in a stepwise fashion. As with elephants, GPS trackers may be used to track the first individuals. Meanwhile, our dedicated team of scientists is furthering real-time acoustic monitoring technologies for advanced tracking capacities.

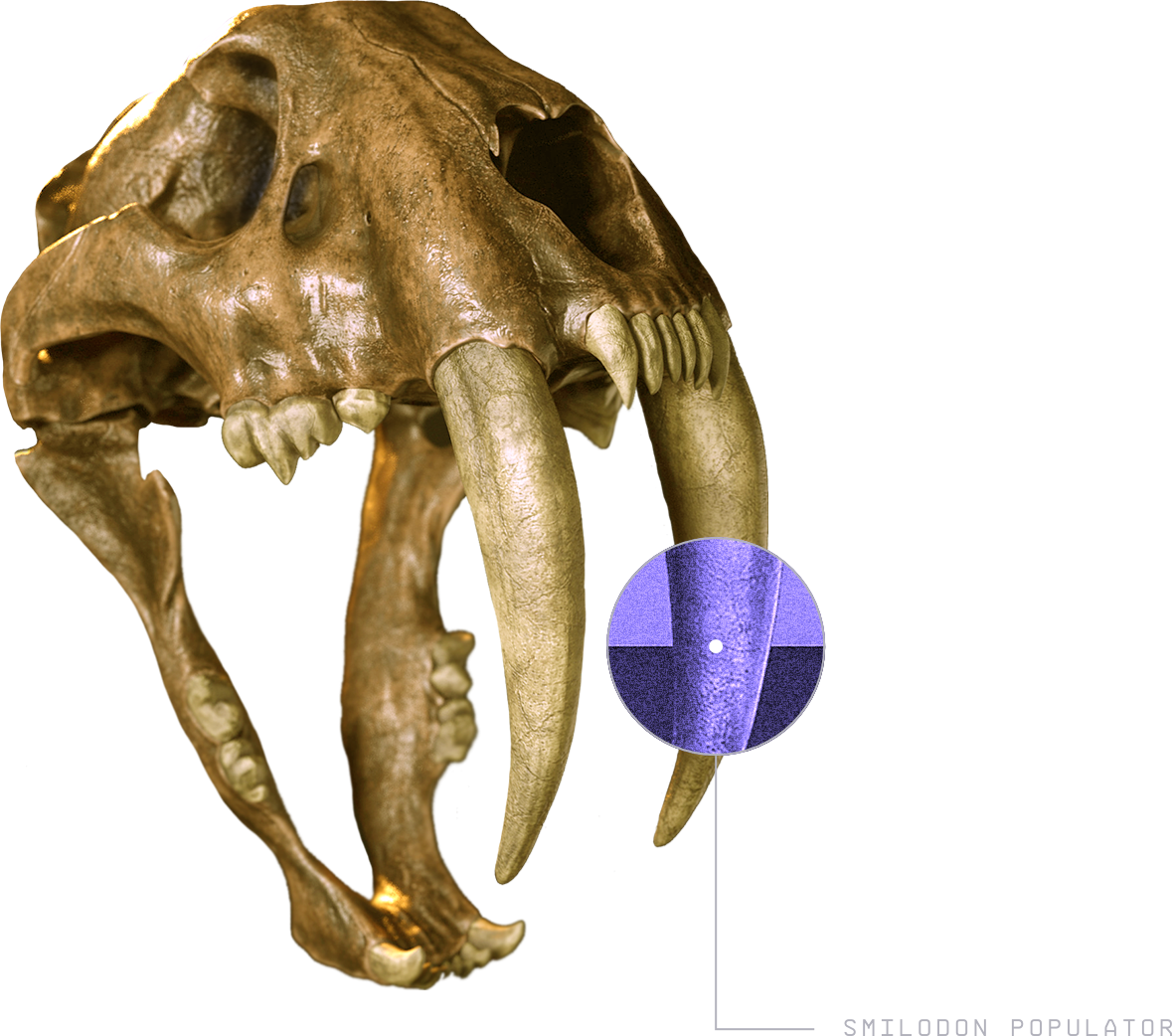

Dire Wolf

The dire wolf (scientific name Aenocyon dirus) was a large canid species that lived in North America during the Pleistocene ice ages. Dire wolves were apex predators that roamed across the American midcontinent, with fossils dating back approximately 250,000 years. Despite popular misconceptions stemming from fantasy literature and television shows like Game of Thrones, dire wolves were real animals that played an important role in prehistoric American ecosystems.

Yes, dire wolves have returned in 2025. On April 7, 2025, Colossal Biosciences announced the successful rebirth of the dire wolf, marking the world’s first de-extinction of an animal species. Three healthy dire wolf pups—two males named Romulus and Remus (born in October 2024) and a female named Khaleesi (born in January 2025)—are now living in a secure 2,000 acre preserve under careful monitoring and care.

Yes, dire wolves have been successfully brought back from extinction through functional de-extinction. In April 2025, Colossal Biosciences announced the birth of three healthy dire wolf pups—the first-ever de-extinct animals created through advanced genetic engineering.

However, it’s important to understand that true de-extinction doesn’t mean creating an exact replica of an extinct species, which is impossible. Instead, Colossal defines de-extinction is defined as “the process of generating an organism that both resembles and is genetically similar to an extinct species by resurrecting its lost lineage of core genes; engineering natural resistances; and enhancing adaptability that will allow it to thrive in today’s environment of climate change, dwindling resources, disease and human interference.”

Colossal’s dire wolf achievement represents true functional de-extinction, not simply cosmetic modifications to existing species. The definition of ‘species’ remains one of the most debated topics in biology, with over 30 different species concepts used by scientists, from biological to phylogenetic, morphological, and ecological concepts.

These animals are called dire wolves because they’re derived from ancient dire wolf DNA. They look like dire wolves and express genes specific to dire wolves that have not existed for over 12,000 years.

Learn more about de-extinction.

No, the dire wolves will never be rewilded. Given the small number of individuals and the complexity of reintroducing an extinct species, Colossal’s dire wolves will remain in their secure ecological preserve throughout their lives. The project’s value lies in advancing de-extinction technologies, benefiting critically endangered species like the red wolf, and demonstrating what’s possible through cutting-edge biotechnology rather than direct ecosystem restoration through rewilding.

Until April 2025, dire wolves had been extinct for approximately 12,000 years, with no credible evidence suggesting any natural populations survived into the modern era. However, through advanced genetic engineering and cloning techniques, Colossal Biosciences has successfully brought back dire wolves, creating the world’s first functionally de-extinct species. Three healthy dire wolf pups—Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi—are now thriving under careful monitoring in a secure 2,000 acre preserve.

Woolly Mammoth

Both nature (genes) and nurture (environment) influence how an organism acquires knowledge in early development.

Given that woolly mammoth genomes are genetically modified derivatives of the Asian elephant genome, the woolly mammoths will retain many of the same genetically-encoded behaviors—including intuitive capacities for navigation, foraging, and survival.

Their surrogate Asian elephant mothers will also teach the young all their elephant ways, and on-the-ground animal behavior specialist teams will provide additional support: while leveraging the expertise of our elephant reproductive science specialists Dr. Wendy Kiso and Dr. Thomas Hildebrandt, we will continue to collaborate with conservation groups, such as Elephant Havens, which have substantial experience in elephant rearing.

Following our engineering of multiple carefully selected cold-adaption traits, not only will the woolly mammoth be adept at thriving in current cold Arctic conditions, it will also be able to dynamically acclimate to environmental changes.

Woolly mammoths were highly adaptable, traveling across a range of latitudes. Much like modern-day elephants, they had far-ranging migration patterns, adapting their diets and behaviors to the different climates they encountered. Their remains have been found as far south as the Shandong province of China and Spain.

The woolly mammoths will also naturally evolve to adapt to their environmental context through genetic (genes actually changing across generations) and epigenetic changes (genes learning to turn themselves on and off in response to environmental needs).

Similarly, after the bucardo went extinct from the French Pyrenees, another subspecies of ibex was reintroduced there in 2014. Though it was hypothesized that no other type of ibex could survive in the arid, high altitude conditions of the bucardo’s range, the ibex is currently thriving. It is even beginning to develop the defining features of the bucardo with each new generation, growing increasingly well cold-adapted while fulfilling its original ecological role.

The genome of the woolly mammoth will be endowed with all the same baseline genetic immunity as that of its host genome species, the Asian elephant.

However, research has shown that molecular evolution has led to differential inflammatory responses to immune threats in Asian versus African elephants—resulting in increased infectious disease susceptibility in Asian elephants, including a greater genetic susceptibility to elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus (EEHV).

Not only will the woolly mammoth be genetically endowed with a baseline level of immunity to contemporary pathogens, but we will enhance its immune system by identifying the genetic mutations that create susceptibility to EEHV in elephants, and eliminating them across all proboscideans—including extant elephants and de-extinct woolly mammoths.

As new challenges arise, we will continue to leverage our sequencing and gene editing technologies to keep our populations healthy and thriving.

We recognize that woolly mammoth remains are being poached at increasingly high rates—leading to a Siberian woolly mammoth tusk gold rush. Tusks can be modified as needed to minimize their allure to poachers.

Once ready for rewilding, the first woolly mammoths will be spread across small, enclosed regions enabling their close tracking. Next, they will be introduced to the Arctic at large in a stepwise fashion. As with elephants, GPS trackers may be used to track the first individuals. Meanwhile, our dedicated team of scientists is furthering real-time acoustic monitoring technologies for advanced tracking capacities.

Thylacine

The thylacine is an extinct marsupial, commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger or the Tasmanian wolf, that was native to the Australian mainland and the islands of Tasmania and New Guinea.

As a carnivorous apex predator, it was a keystone species in the Australian ecosystem with a critical role in regulating its ecosystem by controlling prey species populations, minimizing the effects of invasive species, and removing weak or sick animals.

The last known live animal was captured in 1930 in Tasmania and went extinct in a zoo in 1936.

More information on the thylacine and its history can be found here.

We first plan to reintroduce the thylacine to the southeast Australian island of Tasmania, after which we will reintroduce it to mainland Australia.

We will strategically select locations for the reintroduction of the thylacine that will not interfere with the lives of local Aboriginal communities. These locations will also ensure the presence of sufficient mesopredators to hunt.

Our goal is to ensure that the thylacine takes up its functional role as a unique carnivorous marsupial apex predator within its native ecosystem.

Our embryology and animal husbandry team of experts will use in-vitro fertilization to implant our thylacine embryo into a dunnart for the very initial stages of gestation.

Marsupials however, including the dunnart, give birth to an immature young, about the size of a grain of rice. To continue to gestate, they need to travel to the mothers’ pouch and latch onto a nipple. We are therefore working to develop an ex-utero pouch to transfer the embryo to for the remainder of the maturation period of the thylacine.

We encourage you to read through the details of this fascinating process here.

The de-extinction of the thylacine, which has been spearheaded by Andrew Pask of the University of Melbourne for the last two decades, requires 10 distinct steps.

The genomes of the thylacine and one of its closest living Dasyurid relatives need to be sequenced, after which marsupial cell lines must be established before beginning to gene edit the hundreds of thylacine loci into a host genome. Thereafter, we must generate the thylacine embryo, implant it into a surrogate dunnart mother for gestation (8-42 days), and transfer it to an external artificial pouch for maturation.

As firm believers in radical transparency, we will publicly share all significant progress through this process.

Both nature (genes) and nurture (environment) influence how an organism acquires knowledge in early development.

Given that the thylacine’s genome will be adapted from those of its close Dasyurid relatives, it will encode behaviors intrinsic to marsupials still of relevance to the Tasmanian habitat which has remained relatively unchanged since the thylacine’s extinction in 1936.

Additional behaviors will be supported by on-the-ground animal behavior specialist teams. We will channel our animal husbandry efforts, in partnership with universities, zoos, governments, and wildlife preservations groups such as re:wild and WildArk, to raise a healthy population of thylacines in safe conditions. Once mature and ready to be re-introduced into the wild, we will follow the path of our rewilding partners at Aussie Ark, experts at successfully re-introducing endangered species.

Throughout the entire process, our main priority remains to ensure the safe and ethical rewilding of the thylacine to its native habitat.

The dingo is a human-introduced species that never made it to Tasmania. Across Tasmania, the thylacine was the apex predator.

As for mainland Australia, while the dingo is present as an apex predator, the thylacine was around for far longer than the dingo. The dingo arrived in Australia just around 4,000 years ago while the thylacine’s lineage dates back to 160 million years ago. The thylacine was the land’s native species bred over millions of years of evolution to fulfill its unique ecological role there.

In addition, the dingo and thylacine occupied different ecological niches. The thylacine had a greater bite force and was likely a smaller game hunter than the dingo.

Given its ancient, irreplaceable ecological function, the thylacine is an exemplary candidate for de-extinction, and it is our responsibility to bring it back.

Dodo

The dodo is an extinct flightless bird endemic to the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. Inhabiting the woods in the drier coastal areas, and having an abundance of food and a lack of predators, it is believed that the dodo lost the need for flight and became well adapted as a flightless, ground-dwelling bird.

The first recorded mention of the dodo was by Dutch sailors in 1598. In the following years, dodos were hunted by sailors and their eggs and chicks were eaten by rats, which hitched a ride to Mauritius with the European explorers. At the same time, the dodo’s native habitat was being harvested. The last widely accepted sighting of a dodo was in 1662.

More information on the dodo and its history can be found here.

Although scattered reports describe mass killings of dodos for ships’ provisions, archaeological investigations have found scant evidence of human predation. The human population on Mauritius (an area of 1,860 km2 or 720 sq mi) never exceeded 50 people in the 17th century. People did, however, introduce other animals, including dogs, pigs, cats, rats, and crab-eating macaques, which plundered dodo nests and competed for the limited food resources.

At the same time, humans destroyed the forest habitat of the dodos. The impact of the introduced animals on the dodo population, especially the pigs and macaques, is today considered as severe as that of the hunting. Rats were perhaps not much of a threat to their nests, since dodos would have been used to dealing with local land crabs, but one account states that the clutch consisted of a single egg, which can be an immense extinction pressure when eggs are lost.

Today, the dodo is the most famous species known to have been driven to extinction through human activity. Dodos disappeared over a century before Cuvier proved the reality of extinction, but were only one of a huge number of species that died out following early European expansion around the globe.

Repeated settlement changes on Mauritius during the seventeenth century led to ‘cultural amnesia’ over the dodo’s very existence. By the nineteenth century, the dodo had become widely regarded by European scientists as a mythical creature. A series of scientific and socio-cultural hurdles had to be overcome before dodos would be appreciated by the general public as an icon of human-caused extinction.

The dodo’s posthumous celebrity as the symbol of human driven extinction places a responsibility on us to return them to the habitat they once inhabited peacefully.

Similarly to other strategies used in conservation, our goal is to fill the niche left by the dodo’s extinction. By engineering a proximal species using the closest living relative, we have an opportunity to create an animal that as closely as possible fills the niche left by the dodo on Mauritius; a modern dodo.

We encourage you to read through the details of our de-extinction process or watch a video here.

Understanding and re-writing tens of thousands of years of evolution won’t be fast or easy. Executing the steps described in our high level de-extinction process, and predicting how mutations affect adaptation and speciation will be imperfect. We aim to assess our engineering efforts at the two year mark to better understand what additional engineering efforts may be required, if any.

Birds are among the most threatened groups of animals on the planet today. De-extinction of the dodo will provide a platform to develop technologies that will enable bioengineering-based conservation of living avian species.

We will begin by learning how to culture the cells of pigeons and other living birds. These cells will lend themselves to testing reproductive technologies that can be applied to protect threatened bird species or populations.

Our genome engineering tools will be useful to help threatened bird species adapt to ongoing changes to their habitats. In doing so they will rescue fragile ecosystems where the loss of a species may interrupt food webs and lead to extinction cascades. Our technologies will also enable the revival of recently extinct species, helping to restabilize ecosystems that have not yet recovered from those extinctions.

Conservation

Born out of Colossal Biosciences, the Colossal Foundation is a 501(c)(3) dedicated to supporting the use of cutting-edge technologies to conservation efforts globally to help prevent extinction of keystone species. The organization deploys cutting-edge de-extinction technologies and support to empower partners in the field to reverse the extinction crisis.

Our mission is to make extinction a thing of the past. Colossal creates technological innovations to restore extinct species, protect endangered ones, and rebuild ecosystems that support the continuation of life on Earth. Our non-profit arm, the Colossal Foundation, is focused on rapidly flowing Colossal’s technological advancements to partner-led conservation initiatives around the world.

Learn more about conservation at Colossal.

Reintroducing a keystone species into its original, native habitats—within which it plays a key functional role—is not only constructive, but critical to the healthy function of the ecosystem and its floral and faunal species. This strategy forms a core pillar of rewilding, a global movement to restore ecosystems which has been met with tremendous success in the last few decades.

The reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the 1960s is one such example. Without the checks and balances of the wolf as apex predator, Yellowstone grew rampant with deer, whose overgrazing compromised the fragile balance of the ecosystem. Nearly 70 Canadian wolves were brought back to the park—galvanizing a trophic cascade which rebalanced the Yellowstone landscape—and as of December 2021, the greater Yellowstone region harbors over 500 wolves roaming a vibrant ecosystem, brimming with life.

Beyond rewilding, from the inception of our vision at Colossal to the final reintroduction of de-extinct species into their native habitats, every step of the way is well-informed, thoughtful, and intentional.

Science & Technology

CRISPR is a Nobel Prize-winning technology used for recognizing and cutting a specific code of DNA inside the cell. CRISPR technology was first observed in bacteria, but scientists have been able to re-engineer this CRISPR technology to work in human and animal cells.

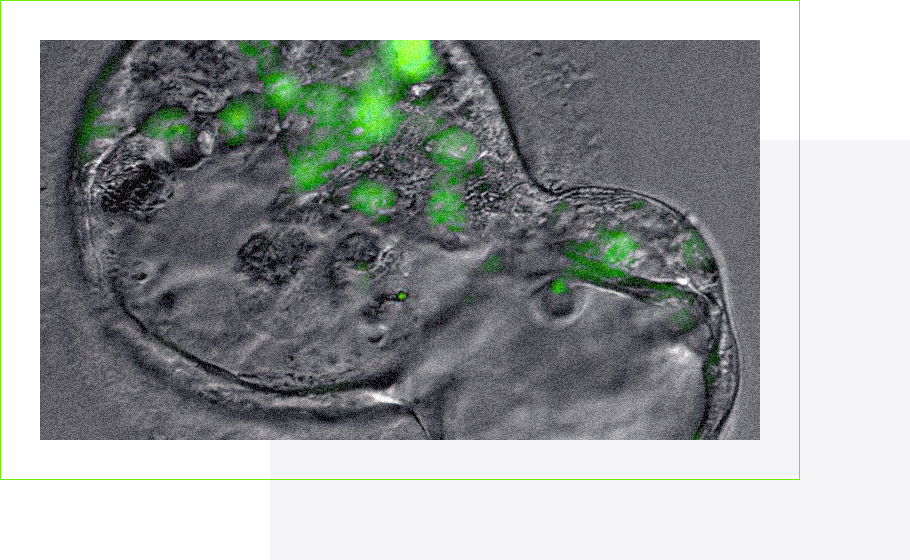

In mammalian cells (such as those of an elephant or a woolly mammoth), classic CRISPR works with a Cas9 enzyme, a guide RNA and a donor DNA fragment to modify genes. CRISPR/Cas9 recognizes a specific DNA sequence where the Cas9 enzyme will cleave close to an adjacent identifier DNA sequence. Once this DNA is cut, synthetic laboratory-made DNA can be re-inserted in its place.

At Colossal, this enables us to insert specific characteristics into a species’ DNA—leading to the generation of a close approximation of an extinct species’ genome. We encourage you to get curious about the extraordinary science and applications of CRISPR here.

Born out of Colossal Biosciences, Form Bio is a new, cutting-edge research and discovery platform for life sciences professionals in industry and academia. With the most accessible, comprehensive and collaborative platform in the field, Form empowers scientists to efficiently and effectively harness the proliferation of data and computing power that has transformed the science of discovery.

Form offers end-to-end integration of the discovery process with intuitive and easy-to-use software applications, combined with an open and adaptable collaborative environment.

Scientific

PAPERS

Read various peer-reviewed scientific papers on rewilding, ecosystem restoration, de-extinction, and conservation.

Scientific Papers Archive

Pleistocene Arctic megafaunal ecological engineering as a natural climate solution?

A palaeontological perspective on the proposal to reintroduce Tasmanian devils to mainland Australia to suppress invasive predators

Megaherbivores Modify Trophic Cascades Triggered by Fear of Predation in an African Savanna Ecosystem

Ecological and evolutionary legacy of megafauna extinctions

Effects of gray wolf-induced trophic cascades on ecosystem carbon cycling

Rewinding the process of mammalian extinction

Megafauna and ecosystem function from the Pleistocene to the Anthropocene